In 1912, Margaret Sanger was living in Manhattan with her husband Bill and their three children. She and Bill dabbled in radical politics, inviting socialists, anarchists, Wobblies, and intellectuals into their home. They debated issues with the likes of Big Bill Haywood, Emma Goldman, and Jack Reed. Arguing fiercely, they were all so determined to change the world in those days.

In 1912, Margaret Sanger was living in Manhattan with her husband Bill and their three children. She and Bill dabbled in radical politics, inviting socialists, anarchists, Wobblies, and intellectuals into their home. They debated issues with the likes of Big Bill Haywood, Emma Goldman, and Jack Reed. Arguing fiercely, they were all so determined to change the world in those days.

Sanger worked as a nurse, specializing in obstetrics. She visited her pregnant patients in their homes, a woman’s bedroom being much preferred for lying in than a hospital. Many were middle-class wives of lawyers, salesmen, and clerks, but calls from the tenements of the Lower East Side drew her as if by some magnetic force.

There she saw the wretchedness and hopelessness of the poor. She saw how pregnancy was a chronic condition for these women, and an impoverishing and debilitating one. Hearing a nurse was in the building, other wives congregated around her. “Tell me something to keep from having another baby,” each one begged. “We cannot afford another one yet.”

One evening a summons to Grand Street transformed Sanger’s life. The patient was a twenty-eight year old Russian woman named Mrs. Sacks. Her husband Jake was a helpful and loving man, but his trifling earnings could hardly support the three children the couple already had, the youngest only one year old.

One evening a summons to Grand Street transformed Sanger’s life. The patient was a twenty-eight year old Russian woman named Mrs. Sacks. Her husband Jake was a helpful and loving man, but his trifling earnings could hardly support the three children the couple already had, the youngest only one year old.

Desperate to prevent the fourth child growing in her belly, Mrs. Sacks had tried to stop it with drugs and purgatives neighbors suggested. Finally a sharp instrument did the job. Now septicemia had set in. With Sanger nursing her tirelessly for three weeks, Mrs. Sacks recovered. But when Sanger told a visiting doctor how worried the woman was about another pregnancy, he turned to Mrs. Sacks and said, “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.”

“He can’t understand,” Mrs. Sacks said to Sanger afterward. “He’s only a man. But you know, don’t you? Please tell me the secret, and I’ll never breathe it to a soul. Please!”

But how could Sanger tell the poor woman something she didn’t know herself? Three months later, Jake Sacks phoned Sanger, begging her to return. Sanger climbed the dingy stairs of the tenement once again to find Mrs. Sacks in a coma. She had tried to terminate another pregnancy. Ten minutes later she died.

Sanger folded the woman’s hands across her breast, drew a sheet over her pallid face as Jake wailed, “My God! My God!” Sanger left the desperate man pacing and walked home through hushed streets. She contemplated the women she had seen writhing in pain, the babies naked and hungry and wrapped in newspapers for warmth, the children with pinched faces and scrawny hands crouched on stone floors. And the coffins, white coffins, black coffins, coffins passing endlessly.

So much suffering. Her nursing delivered only palliatives to ease the suffering. Her treatment did nothing to prevent it. Sanger vowed no more. She was finished with nursing. From then on she would seek out the root of the evil, the endless cycle of pregnancies that brought to mothers miseries as vast as the sky. And so began the battle she would wage for the rest of her life.

So much suffering. Her nursing delivered only palliatives to ease the suffering. Her treatment did nothing to prevent it. Sanger vowed no more. She was finished with nursing. From then on she would seek out the root of the evil, the endless cycle of pregnancies that brought to mothers miseries as vast as the sky. And so began the battle she would wage for the rest of her life.

For six months Sanger searched for an answer to the question so many women had asked: “How can I keep from having another baby?” She visited dozens of libraries, read volumes from Thomas Malthus on population to Havelock Ellis on sexuality. She spoke to physicians, who gave her useless information. She sought out progressives, socialists, others concerned for the poor.

They only warned her about the laws against distributing contraceptive information. “Comstock’ll get you,” they told her, referring to the notorious vice hunter. “Wait for the vote,” suffragists said. And from others “Wait until women have more education.” Or wait until the socialists are in power, or wait for this or for that. “Wait! Wait! Wait!”

At times, the only words of encouragement came from her Wobbly friend, Big Bill Haywood. When she concluded that no practical contraceptive information could be found in America, he told her to look in Europe.

In October 1913, she took her family, researching in England, France, and Holland. She learned much about European contraceptive methods over two months. Then she returned home with her children, leaving husband Bill behind to pursue his art career in Paris.

In October 1913, she took her family, researching in England, France, and Holland. She learned much about European contraceptive methods over two months. Then she returned home with her children, leaving husband Bill behind to pursue his art career in Paris.

Through it all, Sanger embraced what she took to be a woman’s duty: “To look the world in the face with a go-to-hell look in the eyes; to have an idea; to speak and act in defiance of convention.” And back in New York, she did. From her small Manhattan apartment she launched her journal The Woman Rebel.

“Because I believe that woman is enslaved by the world machine, by sex conventions, by motherhood and its present necessary childrearing, by wage-slavery, by middle-class morality, by customs, laws and superstition,” she explained in the inaugural issue of March 1914.

Within days, newspapers reported The Woman Rebel had been barred from the U.S. mail under the Comstock law and that Anthony Comstock was on her trail. Thus began the war between Sanger and Comstock that would last until Comstock died in 1915, days after convicting Sanger’s estranged husband Bill of handing his agent a pamphlet on birth control.

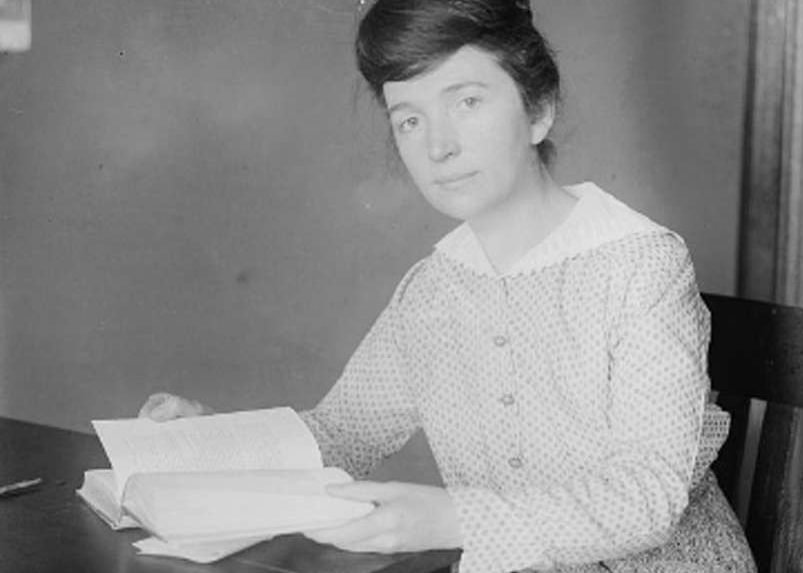

Illustrations, from above: Margaret Sanger in 1916 (Library of Congress); Jacob Riis photo “A Family In Its Tenement Apartment, 1910; Lewis Hine’s “View of Tenement Life on Elizabeth Street, Lower East Side,” ca. 1910 (Library of Congress); and the inaugural issue of Margaret Sanger’s The Woman Rebel.

Recent Comments