If you were walking in Lower Manhattan in the mid-1950s and happened upon a dead-end street of warehouses named Coenties Slip, you would have stumbled upon a “Canalboat Village” – a cluster of barges which had once hauled limestone from Vermont and oysters to Essex, NY, now permanently moored.

If you were walking in Lower Manhattan in the mid-1950s and happened upon a dead-end street of warehouses named Coenties Slip, you would have stumbled upon a “Canalboat Village” – a cluster of barges which had once hauled limestone from Vermont and oysters to Essex, NY, now permanently moored.

By the 1940s, the Champlain Canal had been displaced by the railroad as the fastest and least expensive method of shipping goods from the Champlain Valley to New York City and the families – men, woman, children, pets – who occupied the boats and who had once made livings as “canallers,” were likewise moored, permanently. Despite the fact that they had lost their livelihoods, they never moved to dry land.

A new exhibition at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in Vergennes, Vermont, “Underwater Archaeology: Diving into the Stories of People and Canal Boats on Lake Champlain,” sheds welcome light on the people who lived and worked on the canal boats during their heyday, connecting archaeological evidence to the stories of the people who owned and operated the boats and to the histories of the communities that prospered from the canal trade.

“The Lake Champlain canal sloops and schooners or sailing canal boats – vessels with collapsible masts unique to this transportation corridor – were the tractor trailers of the day. The economy could not have functioned without them,” says Chris Sabick, the museum’s executive director.

According to Russell Bellico, the Hague resident who wrote about sailing canal boats in his book Sails and Steam in the Mountains (Purple Mountain Press, 2001) and edited the journals of one 19th century canal boat owner, the boats not only transported cargoes of stone, iron, coal, lumber and agricultural commodities to urban markets, they brought the world’s luxuries and manufactured goods to communities on both sides of Lake Champlain.

Unlike most of the 19th century maritime industry, which was dominated by men, the sailing canal boats were family affairs – not only operated by the families who lived aboard the boats, but family-owned.

Unlike most of the 19th century maritime industry, which was dominated by men, the sailing canal boats were family affairs – not only operated by the families who lived aboard the boats, but family-owned.

The independence of the sailing canal boat owners and operators owed much to the fact that they did not need to be towed while sailing the lake, said Russ Bellico. Nevertheless, “Living on a sailing canal boat involved hard work – finding freight, loading and unloading, and the risk of accidents, sinking, and financial failure,” he said.

The sailing canal boats evolved to take advantage of the construction of the Champlain Canal. Completed in 1823, the canal connected Lake Champlain with the Hudson River and the Erie Canal and opened the Champlain Valley to the national and even international marketplace.

“No longer did the investors and merchants have to ship their cargo to Whitehall, load it onto wagons and have it dragged 45 miles to the Hudson River, where it would be loaded onto another boat sailing down to New York Harbor,” said Sabick. “You could load up at the dock in Essex or some other inland port and send the cargo directly to market, saving time and money.”

(The need for such a canal was self-evident. In the 1780s, early Champlain Valley settler William Gilliland mused, “how much more valuable [our lands will be] when inland navigation [is possible].”)

On the open waters of Lake Champlain, the captains unfurled the sails “if the winds hold fair,” as the canallers put it. Upon reaching the canal, centerboards and leeboards were retracted and masts were lowered and laid flat; the vessel was transformed into a typical canal boat, towed by horses or mules.

On the Hudson, the barges might join “a tow” of a dozen or more boats hitched to a steamboat bound for New York. According to Sabick, the construction of the canal and then its expansion in the 1860s and 1870s, which accommodated even larger sailing canal boats, reduced the costs of shipping goods to market by 90%.

The underwater archaeologists at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum have closely studied the wrecks of the canal boats that lie at the bottom of Lake Champlain. “Vessels sank for a variety of reasons: storms, structural failure, collisions, fire, negligence. Many appear to have been intentionally sunk or abandoned along the lakeshore,” said Sabick.

According to Sabick, the wrecks are in various states of preservation, some partially submerged, others half buried in sediment. Not only have they yielded information about specific canal boat types, but they are among the best sources of information about the shipbuilding technology of the era, said Sabick.

And in the course of excavating the shipwrecks, the archaeologists have “learned a lot about how people lived in the Champlain Valley. For instance, a wreck found near Port Henry loaded with iron stoves and

And in the course of excavating the shipwrecks, the archaeologists have “learned a lot about how people lived in the Champlain Valley. For instance, a wreck found near Port Henry loaded with iron stoves and

cookware manufactured in Troy provides us with information about the kind of cargo the boats brought back to the Champlain Valley,” said Sabick.

They have also discovered canallers’ home goods, toys, tools, and clothes, helping historians reconstruct the lives of those who lived aboard the boats and in canal villages such as the one at Coenties Slip. Artifacts on display in “Underwater Archaeology: Diving into the Stories of People and Canal Boats on Lake Champlain” include a toy boat and a woman’s overshoe recovered from the sailing canal boat General Butler shipwreck just off the Burlington breakwater, an iron kettle from the canal boat Vergennes and a 19th-century cornet from the sailing canal boat O.J. Walker, among other things.

From the oral histories recorded for the exhibition and from sources such as Russ Bellico’s Life on a Canal Boat: The Journals of Theodore D. Bartley 1861-1889 (Purple Mountain Press, 2020), we can

also learn much about their daily lives: attending the Boatmen’s Mission Church at Coenties Slip, for instance.

According to Chris Sabick, “We can also study census records and learn how many people were employed in canal related work, from operating a canal boat to boat building. Essex, for instance, was a center for canal boat construction. That’s fascinating information and well-worth studying further.”

The Lake Champlain Maritime Museum is open daily from 10 am to 4 pm through October 20th. Call (802) 475-2022 or visit lccm.com. for information.

A version of this article first appeared on the Lake George Mirror, America’s oldest resort paper, covering Lake George and its surrounding environs. You can subscribe to the Mirror HERE.

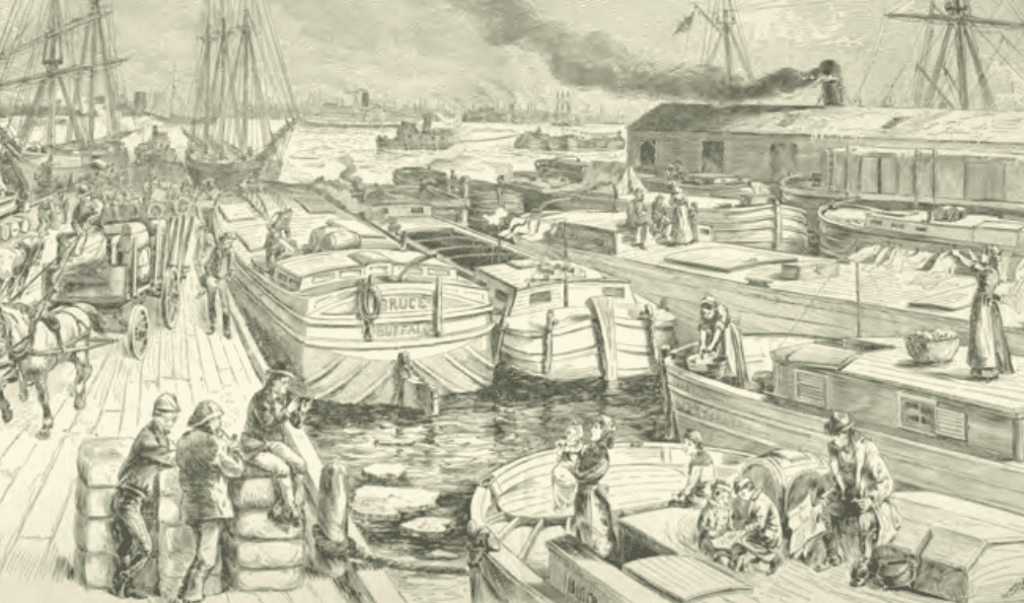

Illustrations, from above: “Laid up for winter – canalboat colony in Coenties Slip, East River,” Harper’s Weekly, 1884 (NYPL); A woman and her family on a canal boat (NPS); and “Canal Boats on the North River, New York” in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, December 25, 1852.

Recent Comments