The Adirondack Park is a unique balance of public preserves and private land, a birthplace of the American wilderness vacation, and a large-scale experiment in humans and nature thriving together (and showing a remarkable ecological recovery).

The Adirondack Park is a unique balance of public preserves and private land, a birthplace of the American wilderness vacation, and a large-scale experiment in humans and nature thriving together (and showing a remarkable ecological recovery).

Reflecting on my own small Adirondack lake community at Twitchell Lake in Herkimer County, social life seems to have passed through at least three phases – among the rugged early sportsmen and women, through the wild “Gilded Age” settlement era, and into our turbulent 20th and 21st centuries.

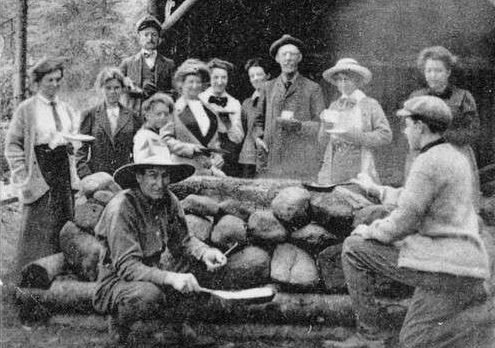

One experience that is common to all three is the Adirondack lean-to and campfire, under and around which heartwarming stories have been shared and passed on. The picture above captures Twitchell’s guide Low Hamilton cooking up a “Slap Jack Luncheon” between yarns, his Lone Pine Tea Room guests and neighbors enthralled.

After thousands of years of Indigenous occupation, seasonal visits by European pioneers trickled in, the earliest dated to 1856 with the tragic drowning of Briggs Wightman. He belonged to a group of Oswego County sportsmen who made the taxing annual trek through Lowville and Number Four to Twitchell Lake, laying out traps on a six-mile trail which forked south from the rough Carthage and Champlain Road.

There they pulled out huge native brook trout and picked off deer herding along the shoreline. This sad story revealed a fragile web of social relationships that tied Twitchell tenuously at this time to the outside world, the Adirondack guide at its center.

Early guide Amos Spofford navigated this wild terrain without a map, bearing news about hunting and fishing conditions, and when and where to avoid a prowling black bear or mountain lion. Notified by Orville Bailey, lying sick in their Rock Shanty along that remote stretch of road, that Briggs “was absent three days,” Amos enlisted four hunters to search for the missing man.

Sighting him lifeless beneath a hole in the ice, wolves circling and howling, Amos recruited six more hunters and guides to carry the body out to Lowville and notify next-of-kin.

An early social hub emerged on Twitchell’s shore in 1870 when guide Hiram Burke built the crude log shanty pictured in this print, slanting behind a cluster of Indian Pipes. Copenhagen, NY, native Charles Twitchell was rumored to have helped harvest the logs for this project.

Hiram was one in a family of guides headed by Chauncey Smith. Hiram spent off-seasons manufacturing hand-made fur gloves, during the 1883 season selling “twelve saddles of venison” in Lowville for one Twitchell hunting party.

Hiram was one in a family of guides headed by Chauncey Smith. Hiram spent off-seasons manufacturing hand-made fur gloves, during the 1883 season selling “twelve saddles of venison” in Lowville for one Twitchell hunting party.

This Oswego group helped Chauncey in 1859 erect “a comfortable woods shanty, for guests, with stabling attached, at the South Branch of Beaver River.” This shanty was 18-miles east of Chauncy’s No. 4 home, housing sportsmen and women on their annual summer or winter quests. From that remote stop on the C-C Road, a wagon route carried fishing and hunting parties to the Burke cabin on Twitchell Lake.

Several of these groups left a vivid record of their social interactions, the first in a lengthy 1874 Journal & Republican article titled “North Woods.” The mystery writer of this fascinating article veiled members of his party as characters in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales.

I uncovered his identity as Copenhagen’s John C. Wright in “Mystery Writer’s Tramp to Twitchell Lake.” John lived next door to Urial, Erastus, and Jerome Twitchell. Regrettably, he kept the secret of how this farming family became namesake to a remote lake 50 miles to the east. Three members of John’s party, I discovered, were Twitchell relatives by marriage.

But John absolutely reveled in the social benefits experienced in their two-week stay in the Hiram shanty. “As for fish, we had a plenty, for our literary man more than sustained his former prestige as a fisherman … In due time we arrived home, feeling renewed and invigorated as if we had a new lease on life, well satisfied that our sojourn in the woods was not without profit and pleasure.”

Not surprisingly, this became an annual trek for John and his Copenhagen compatriots for eight years, cementing a social tie during the sporting era between that Lewis County hamlet and Twitchell Lake.

Wright’s fishing party was not the only one seeking escape from the stresses of America’s exploding industrial centers. Hermits like Jimmy O’Kane, squatting by the Carthage and Champlain Road bridge over Twitchell Creek, was rumored to have sought refuge in the Adirondacks as a Civil War draft-dodger. Hermit David Smith was said to be running away from a failed marriage.

In 1879 a crew for Verplanck Colvin’s Adirondack map team based its operation at the Burke shanty. Headed up by a young Union college grad named Frank Tweedy, their summer task was to get an accurate update of the western boundary to the Totten & Crossfield Purchase for that important map. One of the earliest and largest Adirondack land transfers, that Totten & Crossfield line passed just north of Twitchell.

In 1879 a crew for Verplanck Colvin’s Adirondack map team based its operation at the Burke shanty. Headed up by a young Union college grad named Frank Tweedy, their summer task was to get an accurate update of the western boundary to the Totten & Crossfield Purchase for that important map. One of the earliest and largest Adirondack land transfers, that Totten & Crossfield line passed just north of Twitchell.

Native American guides had accompanied surveyor Archibald Campbell on the original 1772 survey which marked the corner for Townships 42 and 41 in expectation of selling those 189-acre lots to farmers. In 2022, Twitchell Lake explorers with this writer found Tweedy’s survey marker for that corner — pictured here in brass and imprinted with “No. 4.”

Tweedy’s roughneck crew consisted of “flag and chainmen, choppers, guides and packmen, ten all told.” One way he earned their respect was by regularly serving up flapjacks in a frying pan.

His off-duty activities exposed a growing network of social connections in that wild frontier setting, to include weekly trips to No. 4 to exchange updates with his boss, sending his guide to pick up survey equipment repaired in Albany, paying the proprietor of the South Branch shanty for needed provisions, fulfilling a promise to survey a small parcel of land for hotel owner Joe Dunbar on the Carthage and Champlain Road, meeting and interacting with “a party of ladies & gent en route for Salmon Lake,” handling an arrest warrant served on his guide for fishing and hunting violations, responding to a letter threatening a lawsuit for starting a forest fire on the Brandreth Preserve, and meeting a college buddy returning from a fishing trip on Fourth Lake.

His most embarrassing moment that season was his guide’s arrest by Twitchell Lake guide Hiram Burke – the one who OK’d their use of the shanty.

About the same time that Hiram was delivering warrants for the Lewis County Sportsman Association, a “small village” had sprung up less than a mile from Twitchell’s shore, on its east side. Camp #1 housed up to 60 lumberjacks living and working together in what Henry Beach photographed on this classic postcard under the title “A Model Lumber Camp.”

About the same time that Hiram was delivering warrants for the Lewis County Sportsman Association, a “small village” had sprung up less than a mile from Twitchell’s shore, on its east side. Camp #1 housed up to 60 lumberjacks living and working together in what Henry Beach photographed on this classic postcard under the title “A Model Lumber Camp.”

This camp ran year-round for at least four seasons, sending Twitchell’s virgin spruce and white pine down Twitchell Creek to be milled in Beaver Falls. The crash of these giants would have been heard by parties sojourning in the Burke shanty or camping on the lake.

The hamlet of Big Moose was not yet on the map, so the lumberjacks passed their time smoking clay pipes, playing cards on rough-hewn tables, writing letters to sweethearts, sleeping off sore muscles and bones, or venturing to nearby Twitchell to return with two-to-three-pound trout for the camp cook to gut and serve.

Forest Ranger Bill Marleau vividly captured the winter sounds of this early lumbering operation in his Big Moose Station:

Forest Ranger Bill Marleau vividly captured the winter sounds of this early lumbering operation in his Big Moose Station:

“Men worked at night on the landings, using kerosene flares set on long spruce poles. What beautiful music could be heard on below zero nights. The tree popping with frost, the squealing of the sleigh runners on the frozen snow, the squeaking and jingling of the harness on the horses, their snorting with the cold, the men stomping their feet and beating their hands together to keep warm. Frozen words drifting out of men’s mouths off into the frigid night. The noise from one piece of pulp hitting another could be heard almost a mile on such a night.”

A 1900 story in The Albany Argus offered a rare first-hand account of a woman who pioneered each summer at Twitchell Lake in the 1880s. With her father, Grace Dwight Potter founded “The Syracuse Camp” on the lake’s north shore, spending the night on the Carthage and Champlain Road in Joe Dunbar’s hotel after a bumpy buckboard ride through Number Four.

Accompanied by two guides, they camped in a bark lean-to on a high bluff overlooking the lake, meals of venison, trout, and slapjacks prepared outdoors on the campfire.

“Father and I would sit for hours and play poker to the glow of the bonfire and candles, using gun wads for chips,” Grace reported. She noted that everyone carried the mail in those days, the Number Four postmaster requesting they take and deliver mail to any party they might encounter on the way, returning undelivered letters on their return. Communication between parties could take days or weeks.

“Miss Potter declares that those days of mountain life were to her much more enjoyable than the present life in the Adirondacks which like nearly all other summer resorts is characterized by large settlements of fashion and fads,” the Argus reported.

Through the Settlement Era (1892 to 1906)

Through the Settlement Era (1892 to 1906)

The game-changer which ushered in Twitchell’s settlement era was William Seward Webb’s “fairytale railroad.” Webb became owner of Twitchell Lake’s in early 1891 as he purchased large tracts of land as right-of-way for his line.

Hiram Burke had to get special permission from the landlord to keep using his shanty, in exchange for becoming a lake watchdog. And sportsmen now needed written approval from Webb’s Nehasane Park Association to fish or hunt.

In 1896, Webb had all Township 8 lakefront land surveyed by David C. Wood, Twitchell sliced up into 171 hundred-foot lots. Identified on the map are seven pioneers who purchased from Webb, two hoteliers (Skilton and Covey), three clergymen (Jordan, Noble and Stockdale), a banker (Holmes), and a real estate broker (Thistlethwaite). By 1901 there were a total of six camp owners on Twitchell Lake.

Social development followed, fast and furious. The hamlet of Big Moose grew up around the station in just a matter of months, the rugged six-mile trails to Twitchell from the north replaced by a rough two-mile wagon-road ending at a Public Landing on the south shore. Now on days off the lumberjacks blew their paychecks in Big Moose bars. This was the era of the Great Camp, the Gilded Age hotel, and ladies joining their husbands with travel trunks and children-in-tow.

The postcard here has two hotel drivers – Earl Covey and John Denio – posing on Twitchell Creek bridge with their families. These horse-drawn buckboards were extremely busy with up to ten trains bringing tourists to the Adirondacks by 1910. The Big Moose Supply Company was formed to move people and goods between the train station, local hotels, private camps, general stores, and lumber camps.

The postcard here has two hotel drivers – Earl Covey and John Denio – posing on Twitchell Creek bridge with their families. These horse-drawn buckboards were extremely busy with up to ten trains bringing tourists to the Adirondacks by 1910. The Big Moose Supply Company was formed to move people and goods between the train station, local hotels, private camps, general stores, and lumber camps.

Rev. Dwight Jordan made the first purchase from Webb in April of 1898. He had hunted and fished at Twitchell Lake as early as 1895, inviting fellow pastor Eugene Noble up to fish, catching enough trout to cook for breakfast on the Burke campfire.

Noble purchased his lots in 1900, his “Camp Elbon” completed one year later. Another colleague, Rev. Fairbank Stockdale, purchased his lots in 1901. A fourth clergyman, Rev. Dr. Stephen Herben, presided at the memorial service for Jordan’s wife Louise, and soon he too, became a Twitchell laker, purchasing lots from the Noble family.

All four pastors knew each other from their Methodist Episcopal Association in Brooklyn, NY. Eugene Noble went on to be president of three Colleges, including Dickinson in Carlisle, PA. A sermon by Fairbank’s son George titled “The Ways of Trout and Men” was featured in Old Forge’s Lumber Camp News in August of 1940.

As the four clergy families made their summer retreats from the rigors of big city ministry, they added much to the social fabric of the lake, this dynamic well-expressed by lake historian Bruce Steltzer:

“The four ministers and their families were yearly summer residents and active in the affairs of the lake, hosting sing-a-longs at their camps, joining their camp’s canoes and guide boats together for square dances at the Twitchell Inn and dinners at both the Inn and Skilton Lodge, eating at Myra Hamilton’s Pine Tea Room and eating flap jacks cooked by Low Hamilton, hiking together to East Pond, South Pond, Silver and Terror Lakes.”

“The four ministers and their families were yearly summer residents and active in the affairs of the lake, hosting sing-a-longs at their camps, joining their camp’s canoes and guide boats together for square dances at the Twitchell Inn and dinners at both the Inn and Skilton Lodge, eating at Myra Hamilton’s Pine Tea Room and eating flap jacks cooked by Low Hamilton, hiking together to East Pond, South Pond, Silver and Terror Lakes.”

And this: “Thanks mostly to Francis [Eugene Noble’s son], ours has been a singing family. There’s a large music section in our oral tradition, songs we’ve never written down but we all know. … The primary place for learning songs was the campfire … All the camps on the lake were invited, and the singing went on for hours.”

November 1898 saw two hotel men make large purchases from Webb, Truman Skilton 36 lots on the north end of the lake, Earl Covey 23 lots on the southeast side. Truman Skilton was following his passion for trout fishing and preservation, while also running a Winstead, CT business that marketed fishing gear – reels, lures, fly rods, and tackle, direct and by mail order.

On his 217-acres he built a family lodge and resort “let out to the ‘sports’ who sought peace, tranquility, and trout in the solitude of the Adirondack wilderness,” according to The Reel News. Skilton’s hotel boasted a central three-story main lodge, assorted cottages, a lean-to, storage barn, and this lakeside boathouse with docks, “A Few Good Ones” hanging under the eaves (pictured here). Skilton’s Lodge became a very popular destination for summer visitors and their families.

On his 217-acres he built a family lodge and resort “let out to the ‘sports’ who sought peace, tranquility, and trout in the solitude of the Adirondack wilderness,” according to The Reel News. Skilton’s hotel boasted a central three-story main lodge, assorted cottages, a lean-to, storage barn, and this lakeside boathouse with docks, “A Few Good Ones” hanging under the eaves (pictured here). Skilton’s Lodge became a very popular destination for summer visitors and their families.

Earl Covey became legendary for his half-log palisade-style architecture, erecting many cabins with his son Sumner for Inn guests who fell in love with the lake’s wilderness setting. It was said that Covey put Twitchell Lake on the map with his 18-bedroom Inn and Great Room viewed on this postcard, bear skins part of the decor.

He added a sawmill, icehouse, storage barns, and individual lakeside cottages on most of his 23 lots, water supplied to all of them by a main pipe running under the lake to a reservoir higher up on the opposite side.

Ken Sprague’s “History & Heritage” column in the Adirondack Express offered these insights: “[Covey] was an accomplished square dancer, loved to dance, and as a caller was much in demand. He held weekly dances at the Inn that were not only popular, but very well attended. The Inn became a social center for the community around the lake as a place to go and there was a post office as well as a small grocery on the Inn’s ground floors.”

Twitchell Lake Inn early on became a hub for mail, groceries, music, dance, construction, supply of ice for refrigeration, public meetings, and a schoolhouse for lake children.

The two guides who adopted Twitchell as their home are pictured, Lowell (Low) Hamilton on the left, Francis Young on the right. Between the damming of Beaver River and Webb’s widespread “No Trespassing” signs, Adirondack guides were scouting out new territory for their sports.

Francis built the second camp on the lake and named it “Birch Grove,” recording in his camp Bible, “This book is not to be taken hence, so long as this lodging in the wilderness remains, Sept. 1, 1889.”

In 1901 he obtained a deed from Truman Skilton for the land his cabin sat on. A superb woodsman, he guided for the great American stage actress Minnie Maddern Fiske who vacationed on Big Moose Lake. At 70 years of age, he carried a guide boat to Beaver River and then north to Salmon Lake, a good twelve-mile haul. Twitchell Lake Inn held a weekly Saturday night square dance, where Francis taught many of the young ladies how to do the Schottische – a Bohemian folk dance popular in the 19th-century.

Francis and Low became next-door-neighbors in 1901 when Low bought a parcel of land from Skilton, naming his camp “Lone Pine” for the ancient white pine that towered over the shore. Bea Noble, Eugene’s daughter, said that Low “had a waspish disposition and an acid tongue,” a friend to Francis one day and an enemy the next, but always making up.

Francis and Low became next-door-neighbors in 1901 when Low bought a parcel of land from Skilton, naming his camp “Lone Pine” for the ancient white pine that towered over the shore. Bea Noble, Eugene’s daughter, said that Low “had a waspish disposition and an acid tongue,” a friend to Francis one day and an enemy the next, but always making up.

They challenged each other with who could make the best flapjacks over an open campfire for groups of neighbors, and after a while they both would exclaim with a smirk, “That’s enough, you’ve all had enough.”

Bill Marleau remembered Francis as able “to make snowshoes, repair furniture and build most anything. He was one of the three finest fly fishermen in the North Woods along with Low Hamilton and Reuben Brownell of Twitchell Lake.” Low maintained a tent platform and guide boat at Terror Lake, a handy launch for his sports to hike to distant ponds and lakes with good hunting and fishing.

A third hotel on Twitchell Lake was opened by Low with his wife Mary and daughter Myra. It centered around a “Tea Room” Low built which afforded a beautiful lakeside view, crowning the hotel with its name, “Lone Pine Tea Room.” In addition, he constructed sleeping rooms atop a boat house, winter quarters, guest cabins, a shop and laundry, an icehouse, and quarters for help.

The Hamilton’s served a growing clientele of repeat customers that included sportsmen and women, hunters, fishermen, and hikers. Low cut and maintained a good trail to Big Moose Lake’s North Bay, where “going to Twitchell for tea” became the thing to do. But that was not all, it was common practice at that time to attend services at Big Moose Chapel, hike to Lone Pine for tea and pastries, rent a canoe for dinner at Twitchell Lake Inn, and close the day with a drive back to Big Moose Lake. Low’s work on the Beaver River trail also attracted customers.

The Hamilton’s served a growing clientele of repeat customers that included sportsmen and women, hunters, fishermen, and hikers. Low cut and maintained a good trail to Big Moose Lake’s North Bay, where “going to Twitchell for tea” became the thing to do. But that was not all, it was common practice at that time to attend services at Big Moose Chapel, hike to Lone Pine for tea and pastries, rent a canoe for dinner at Twitchell Lake Inn, and close the day with a drive back to Big Moose Lake. Low’s work on the Beaver River trail also attracted customers.

Myra grew up in this remote location, long winter days and nights spent with her mother Mary in their “winter camp” dug into the side of a hill, a large open kitchen and wood fire burning in the kitchen protecting them from winter winds. There they crocheted doilies, crafted birch bark items and boxes made of porcupine quills and sewed balsam pillows. Myra sold these items in the hotel store and in a souvenir shop in Brooklyn, NY.

Myra’s marketing brochure detailed the menu with “a fresh supply of Huyler’s every week,” the premier producer of chocolate and cocoa at the time. A trail map she drew was included with all nearby trails marked. For those arriving at Big Moose Station, a telephone line called up transportation by horse and buggy, round trip fare 25c. She closed with her own lending library “with its 280 books of latest fiction at the disposal of the public for the small sum of 2c per day.”

By 1901 there were a total of six camp owners on the lake, Rufus Holmes, a banker from Winsted, CT, one of those first seven pioneers. He was a charter member of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, whose object was “the well-being and happiness of the residents and those who visit the region for health and recreation … [and] the preservation of the beauty of our unequalled natural Park with the conservation of the water supply for the rivers and canals of the State of New York.”

William Thistlethwaite scooped up the remaining lots on the lake with plans to log and sell them to interested summer cottage owners. A New York State lawsuit prevented him from cutting all the majestic red spruce and white pine giants along the shoreline.

After camping in tents at Twitchell for two years, the 100-member Men’s Club of the Church of the Holy Cross in Utica purchased three lots from William Seward Webb. Their plan was to build a camp for the club and invite club members to build individual cabins which they could occupy at any time of year in 1902. This club’s minutes reveal just how important its Twitchell outpost had become.

After 1903, a growing list of lots purchased from Thistlethwaite were recorded, adding the following new families to the lake community: George Kellogg and William Meldram (1903), Mary Taffel and Prue Shattuck (1904), Louis Slayton (1905), and Fred Smith (1906). New camps were quickly added along the Twitchell shoreline.

Hoteliers, clergy, and guides were all in the people business, so it is not surprising that their pioneering success and settlement would create a rich social environment on Twitchell Lake. A half-hour boat ride transported a family to the Inn for a Saturday night square dance, or to any one of the many campfire invitations extended during the summer or fall seasons.

But in that era, connection by land was even easier than by water. Webb’s conservation covenant was incorporated into every cottage and hotel deed, with stipulations about public access to all trails on private lands. As a result, there was a public trail circling the lake and passing right through all the private lots. This writer’s grandparents used that trail to tramp to Skilton’s Lodge or Lone Pine Tea Room, getting invitations to tour and visit many of the camp families along the way.

In addition, the Gilded Age saw advances in technology – the horse-drawn buckboard yielding to rail and auto travel, kerosene lamps gradually replaced by electrical lighting, and lake communication aided by a one-wire phone line from the public landing around to the three hotels.

These changes aided social interaction in this remote wilderness setting. Challenged with the problem of climbing the steep hill on Twitchell Lake Road in winter conditions, Earl Covey patented a Polar-Grip snow tire with the assistance of Firestone Tire & Rubber Company. Already a leader in many respects, that raised his social stock with lake residents even further.

This era also saw a community-to-community connection established between Twitchell Lake and a settlement one mile to the west at beautiful Silver Lake. This story began with two boyhood friends from Pennsylvania who grew up hunting, fishing, and canoeing together – James Irwin and George Butler.

This era also saw a community-to-community connection established between Twitchell Lake and a settlement one mile to the west at beautiful Silver Lake. This story began with two boyhood friends from Pennsylvania who grew up hunting, fishing, and canoeing together – James Irwin and George Butler.

Irwin was hired by Webb to run his railroad through Big Moose, where he fell in love with the area around Twitchell and Silver Lakes. Butler joined Irwin in purchasing 336 acres from Webb in 1898, turning to Earl Covey to supervise the building of the camp seen here, constructed from whole logs, a pit for sawing half-logs unavailable in that remote location.

Bill Marleau detailed the Irwin-Butler family connection with Twitchell Lake, particularly with builder Earl Covey and guides Low Hamilton and Francis Young, as he described the first summer occupants in this cabin: “The fireplace was designed by Jim [Irwin] and built by a mason named Kit Van Omum.

Among the original furnishings were four, four-legged stools made by the Twitchell Lake guide, Francis Young and a round table five feet in diameter, built one Sunday by Jim. Latches on the doors were carved by another Twitchell Lake guide, Low Hamilton. An iron stove and other heavy items were hauled into camp on a horse-drawn sled called a “jumper.”

In 1901 Jim’s wife Frances with three small boys, one an infant, took up vacation residence in the camp. A young French-Canadian woman named Rose assisted in housekeeping, and a young Swede named Edwin, engaged to do heavy chores, was lodged in a lean-to across the lake.

A single wire telephone line was run into Silver that year from Big Moose Station so that Jim could keep in touch with his family from his job in Utica and keep in touch with his job when he was at Silver on vacation.

This Twitchell connection was vitally important then and continues today, with technological advances like the telephone and telegraph expanding social possibilities.

On Into the Twentieth Century (1906 to 2000)

On Into the Twentieth Century (1906 to 2000)

A 1912 headline announced an all-lake sporting event which showed just how much this wilderness community had jelled even after the Twentieth Century was plunged into a world war.

“Twitchell Lake Regatta” featured events familiar to us born later in the century such as guide boat rowing, canoe-tilting, ladies canoe paddling, and a children’s rowing contest; but then there were three events which need a little explanation – log riding, hand-paddling, and a “Harlequin” race.

Contest reports from the first category reveal several interesting findings. The children of three lake pioneers won key races, William Covey the lightweight rowing contest, Lois Slayton the women’s canoe race, and Sumner Covey the children’s rowing contest. Evidently, Twitchell pioneers were successfully passing the baton of lake ownership to a new generation, a key function in social life.

The reporter attending the regatta said, “A large and enthusiastic assemblage watched the various events,” despite an impending storm! At this point in time, Twitchellites – some affluent but the majority just making ends meet – were all in. And the three contest judges were clergymen, still a trusted vocation, Rev. Dr. Eugene Noble, Rev. Dr. Stephen Herben, and Rev. William Clarke.

The three less-recognized events offer notable social commentary on the times, Twitchell Lake still surrounded by several logging operations. Logrolling contests were sponsored for many years by competing lumber companies, a tribute to the dangerous exploits of river monkeys who broke up logjams.

This day’s log riding was a huge hit: “Much amusement was afforded by the log riding contest. George Marlow of Big Moose won from W. E. Covey, but Covey maneuvered his treacherous log beautifully. Both men displayed extraordinary skill, riding the logs far out beyond their depth.” The fact that George Marlow, unofficial mayor of Big Moose, won that contest shows just how important the link was between Twitchell and the hamlet linking it to the rest of the world.

Paddling in 1912 was not what we think it might be today. It was a fast-paced and somewhat violent sport which we would call “canoe polo,” featuring teams of around five players, each maneuvering a canoe to be first to get a ball into a goal, paddling with one hand, throwing with the other, and sometimes capsizing.

![]()

![]() It was highly athletic for participants, as spectators shouted and cheered for their teams. This specialized canoe race evolved at a time when canoe-courting was popular.

It was highly athletic for participants, as spectators shouted and cheered for their teams. This specialized canoe race evolved at a time when canoe-courting was popular.

The “Harlequin Race” involved a contest between a competing group of young people donning diamond-patterned outfits and masks not unlike this jester, their attire torn and patched together from scraps of camp cloth.

The clown-like Harlequin character was popularized in Italian theatre where he was known for his acrobatic feats and comic antics, a beloved figure representing creativity, mischief, and joy. It is quite likely that a community member with a theater and arts background entered this event as a counterpoint and relief from a world already bogged down in two years of war.

Twentieth century events shared a sentiment the earlier generations expressed or felt as the source of their love for Twitchell, appreciation for nature and wilderness, relief from the stresses of an overburdened life, or in the words of John Wright, “feeling renewed and invigorated as if we had a new lease on life.”

Myra Hamilton’s sale of souvenirs in Brooklyn acquainted her with a gentleman she invited for a visit to the lake. Upon arrival at Lone Pine, Fred Ellmer’s first words were, “This is where I could spend the rest of my life!” Their 1915 marriage flowered into a life-long partnership managing the Tea Room, after he accepted the mantle of ownership from Low, who at first doubted this city-slicker could handle it.

Fred regularly met the train at Big Moose Station, kept refrigerators iced, handled maintenance problems, led canoe trips and wilderness hikes, shared stories and songs around the campfire, and ferried customers in the Duchess, an old passenger and freight boat about 20-foot long, covered by the wood and canvas fringed top seen here.

Fred regularly met the train at Big Moose Station, kept refrigerators iced, handled maintenance problems, led canoe trips and wilderness hikes, shared stories and songs around the campfire, and ferried customers in the Duchess, an old passenger and freight boat about 20-foot long, covered by the wood and canvas fringed top seen here.

Reflecting on their time together, Fred said: “I gave my guests two weeks of fun. They would say that those were the happiest days of their lives, and the memories of those days would last the whole year.”

Important life events like engagement, marriage, a honeymoon, and spreading a loved-one’s ashes, became regular events as the century marched on. Perhaps the first wedding celebrated at Twitchell united two early lake families in marriage. In 1918, George Herben and Beatrice Slayton shared their vows under the pines between their camps. Other families were similarly united as time went on.

This writer is now fourth generation in a love story shared as a series of articles in New York Almanack. Lucretia Hayes’s parents were regular guests at Twitchell Lake Inn. After meeting Norman Sherry at a wedding in Lockport, NY, and exchanging letters, she invited him up for a 1907 visit on Memorial Day weekend.

Norman proposed over a campfire the couple built in the woods after getting lost returning from East Pond. Norman’s diary makes an exciting read as he describes this unexpected announcement to his Troy family, their Buffalo wedding, and Adirondack Railroad return for an Inn honeymoon.

A 1921 entry in Norman’s diary related regular use of the public trail circling the lake, with rich social connections, “This AM Harold & I tramped along left (northern) side of Lake passing close in rear to the numerous camps; climbed up to Lookout Mt from Brownells & also the ladder to top of tree at outlook giving the fine view to N.E. Then to Lone Pine & returned directly to camp” (May 14) … Lu, Harold & I rowed to Nobles & walked around the camps nearby, calling on Francis Young” (May 15).

Harold was Norman’s brother-in-law, Fay and Mildred Brownell proprietors of Skilton Lodge at that time.

The Covey camp Norman and Lu inherited hosted an all-lake campfire on August 6th with this report of the lively event:

“We invited many campers on the Lake & guests at the Inn to our first Campfire in the place & amphitheater prepared. Chas had superintendence building of the ‘pyre’ & it was a big & fine one. The slanting space cleared was well adapted to the crowd. Counted 15 boats or canoes which we stored or ‘parked’ near the dock. Served popcorn & lemonade. Lucretia counted 62 persons, incl. our 2 camp families.” Chas was a Sherry & Co. salesman who had become a close family friend.

Norman’s 1926 diary attests to the intense competition and financial pressures facing grocers like Sherry & Co. as the Great Depression approached. His Twitchell holiday weekends were his only respite in this chapter of his life.

The depth of this stress surfaced on a Twitchell canoe paddle as Lu challenged him to simplify the scope of his business endeavors. The next morning their spat was settled, but the job strain remained. It is touching that Norman spent that September day with their four children, including one-on-one time with Esther, limited as to her mobility:

“About 10:30 I rowed w. Esther to Lone Pine to get a donkey ride, but could not find ‘Genevieve’ tho’ looked over the vicinity! So substituted ice cream! Four kids & I had nice swim 4:30 PM. At 7:10 I went for bull heads w. Francis & Junior, Jr. caught the only two taken- not biting this evg! Betty went to Allens” (September 3).

“About 10:30 I rowed w. Esther to Lone Pine to get a donkey ride, but could not find ‘Genevieve’ tho’ looked over the vicinity! So substituted ice cream! Four kids & I had nice swim 4:30 PM. At 7:10 I went for bull heads w. Francis & Junior, Jr. caught the only two taken- not biting this evg! Betty went to Allens” (September 3).

Genevieve was the Lone Pine pet donkey youngsters loved to pet and ride.

A shock to his family and Twitchell friends, Norman’s diary went blank on September 17th, the result of his death from a massive heart attack at age 55, no will or life insurance for the family to fall back on.

It is a great testament to two women, Ellen Hayes and Lucretia Sherry, who kept at least one Twitchell lot through troubled times, so that this writer could share his love for the Adirondacks now with a sixth generation. In each of the three eras, Twitchell social life had to weather tragedies like an untimely death, the drowning of a young child, a guide falling off a roof, or a serious hunting accident.

Skilton’s Lodge continued under different proprietors to serve its clientele up to the beginning of the Second World War. Here a Labor Day ca. 1923 letter from Truman Skilton’s niece Lida to her fiancé Sherman a year or two before their marriage gives a humorous glimpse of lake social life:

“I’ve been sitting in the smoke of a huge camp fire and say I’ll smell like a pine cone by the time I get back. I hope you like the balsam I enclose … There are only about 30 cottages and camps around the lake which is four miles long so as we are quite by ourselves, what a corking place to spend one’s honeymoon either early May or late Oct. There are two families here that spend the year around so it wouldn’t be half bad. The big ‘Lodge’ is full and uncle’s other cottages too. The new one isn’t done yet and hence we are all piled into the boat house.”

The dark clouds of war cast a long shadow even on remote Twitchell Lake. William Earl Covey, the popular son of the Inn proprietor, served with high distinction in France, before word came to his parents he had died from the flu pandemic compounded by pneumonia, just after the First World War ended. William’s two summer friends, Francis Noble and George Murray, Army and Navy veterans of the war, planned a memorial bridge by Twitchell Creek falls William loved so much.

Francis and George wanted to commemorate and honor their lost friend, “to preserve that intangible, imperishable bond which makes Twitchell Lake and its memories one of our dearest possessions.” Murray’s family summered in the Twitchell Lake Inn boathouse, George writing about an adventurous trip he took on the train with his buddies, “The Joys of Camping,” now posted on the Twitchell Lake website. A huge crowd gathered for the dedication exercises on August 27, 1921.

Francis and George wanted to commemorate and honor their lost friend, “to preserve that intangible, imperishable bond which makes Twitchell Lake and its memories one of our dearest possessions.” Murray’s family summered in the Twitchell Lake Inn boathouse, George writing about an adventurous trip he took on the train with his buddies, “The Joys of Camping,” now posted on the Twitchell Lake website. A huge crowd gathered for the dedication exercises on August 27, 1921.

The chapel on Twitchell Lake Road shelters a fascinating 20th century story, inspired by Methodist minister Nicola Di Stefano. Pictured here along with the chapel, Nicola immigrated from Sicily at age 16 and ended up pastoring an inner-city church in North Syracuse’s Italian community.

As the Great Depression stuck, he desired to give “fresh air” kids an experience of the beautiful Adirondacks, teaching them to fish and hunt while they learned about God. According to Nicola’s great grandson Joe Addison, he purchased the property the three buildings are situated on for two Italian lace bedspreads.

Built in 1929, the first of the three buildings was Camp Bonafide’s dormitory and kitchen for his guests, now owned by descendant Nick Occhino. The second was built as housing for Rev. Di Stefano, currently owned by the Addison family. The chapel, also in the Addison family, was designed by Nicola’s daughter Myrtle and built by carpenters and masons from his church.

Built in 1929, the first of the three buildings was Camp Bonafide’s dormitory and kitchen for his guests, now owned by descendant Nick Occhino. The second was built as housing for Rev. Di Stefano, currently owned by the Addison family. The chapel, also in the Addison family, was designed by Nicola’s daughter Myrtle and built by carpenters and masons from his church.

Dr. Occhino administered first aid in the late 1950s to this writer suffering from a serious infection. The Occhino and Addison families, Nicola’s descendants, are also a part of the Twitchell Lake community, enjoying its vista and waters along with the rest of us. There is at least a half dozen families with camps on Twitchell Lake Road.

An early effort to tell the Twitchell story was made by long-time chore boy for the Lone Pine Tea Room, Aziel LaFayve, who worked for Fred Ellmers through the thirties and forties. His day was filled with trips to the Public Landing via the Duchess — taking guests on hikes or making sure they caught the late-night train bound for Utica or New York City.

In 1991 he gave a talk at Twitchell Lake Fish & Game Society’s Neighbor Day event titled “Then and Now,” in which he made this perceptive observation about how social life had changed in his time on the lake:

“I believe that the individual camp occupancy differed [then] from that of today. In those days, it seemed that some members of the family were at camp all times throughout the summer. It doesn’t seem to be that way today. There was a variety of social events. They were always interesting and lots of fun. The boat house parties were much like our Neighbor Day except that they took place in the evening.”

The boat house parties Aziel referred to were a tradition that lasted right up to mid-century, when “Stevie” Herben Lewis described “A Twitchell Boathouse” extravaganza. It was held in the Slayton Boathouse. Sheets of plywood were set on sawhorses in the boathouse forming a long table covered by white bedsheets, surrounded by tall stands with large white candles for lighting.

The boat house parties Aziel referred to were a tradition that lasted right up to mid-century, when “Stevie” Herben Lewis described “A Twitchell Boathouse” extravaganza. It was held in the Slayton Boathouse. Sheets of plywood were set on sawhorses in the boathouse forming a long table covered by white bedsheets, surrounded by tall stands with large white candles for lighting.

The sumptuous spread was topped by a surprise desert, Stevie directed on a first motorboat ride to obtain large containers of homemade ice cream at Twitchell Inn. “We were off like rabbits [on] the most important trip of our lives,” she exclaimed, with this reflection afterwards about the whole affair:

“I remember walking out, down to the edge of the dock, turning back to watch, then looking out on the lake … there seemed to be a hundred boats tied and quiet at the dock. I remember feeling that this was the happiest time of my life. I felt that the whole world and all its love surrounded me and would forever and ever.”

The Twitchell Lake Fish & Game Society (TLF&GS) was formed just after the mid-century mark, as lake fishermen were up-in-arms over declines in trout catches amid competition from perch and bullhead populations. Another early complaint had to do with teen hot rodders in boats putting their seniors in jeopardy, to which the club’s first president, Hamilton Allen, responded, “[They] will be responsible for the Twitchell of tomorrow.” After a gentle appeal to the youngsters, all debate rested.

Beyond fish and game, TLF&GS organized many activities and events contributing to social solidarity in the lake community. The second president of the club, Norman Sherry, summed it up this way:

“I envisioned that it would be a genuine improvement association which would be interested in everything that might be good for the property owners. And this, of course, is the way the Club has always been, from holding the annual Neighbors’ Day picnic, to boat and canoe races, auctions, water safety, garbage collection, monitoring Lake-water purity, T shirts, getting out a Who’s Who, and so on.”

Holiday letters were regularly circulated among club members off-season, this one announcing the death of Dr. Beatrice Herben, M.D., sculptress, and philosopher, with this significant note: “Her passing marks the end of an era at Twitchell – an era when staunch old families spent all summer at the Lake, fishing, hiking, singing around campfires, using guide boats for transportation, kerosene for lamp light, and ice houses for refrigeration.”

An article by this writer titled “Twitchell’s Troubled Waters” documents the amazing story about officers and volunteers of the TLF&GS cleaning up a lake swamped by high E. Coli readings in the 1950s.

With Skilton’s Lodge closed and Twitchell Lake Inn on the auction block in 1958, the hotel era was almost over, Lone Pine Tea Room purchased and reopened by Loren and Ethel Kellogg under the name “Lone Pine Kamp.” Run as housekeeping units, it was advertised as “a restful place free of the hustle and bustle of the highway. Open for hunters throughout the hunting season.”

Loren and Ethel’s son Bill took over management of the resort upon Loren’s untimely death. As a TLF&GS president who lent his know-how to many endeavors, Bill stood out as a leader for his maintenance of the dock at the public landing, oversight of the Sunset Parking facility, and planning for the popular annual Neighbors Day event.

Bill’s beloved spouse Judy (Peck) Kellogg subsequently carried on with Lone Pine Kamp after Bill’s untimely death, this beautiful lean-to erected as a memorial to Bill and dedicated in 1987.

Bill’s beloved spouse Judy (Peck) Kellogg subsequently carried on with Lone Pine Kamp after Bill’s untimely death, this beautiful lean-to erected as a memorial to Bill and dedicated in 1987.

“Here one may relax, enjoy food cooked over the ever-present fireplace (a part of every lean-to), and eventually sleep in its shelter to the music of a crackling fire and the usually adjacent brook,” Maurice Lowerre, Jr. said during a dedication ceremony. It is therefore especially fitting that this unique structure so typical of our Adirondacks has been chosen and hereby dedicated to the memory of our friend and neighbor, Bill Kellogg. As we share and use it, his memory will remain with us through the years to come.”

Judy Kellogg is perhaps even better known for her 15-year tenure as Twitchell’s mail lady, a tradition whose inception traced to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, friend to the Allen family, who got the Postmaster General to appoint Fred Ellmers as first mail carrier for the lake.

Judy met the Eagle Bay postmaster at the Public Landing at 10:30 am, Monday through Saturday, July 1 to September 15. “All but a few of the camps are inaccessible by car. Judy makes it easy for them. She drops off the incoming mail and takes the outgoing, all of it done from the end of each dock within a span of seconds,” she told the Adirondack Express in 1992.

This writer remembers Twitchell entertainment from his childhood and teen years in the 50s and 60s, rainy day games of Monopoly, wild family contests of “fighting Canfield,” and skilled shooting in Crokinole, imported to the lake by a French-Canadian lumberjack.

This writer remembers Twitchell entertainment from his childhood and teen years in the 50s and 60s, rainy day games of Monopoly, wild family contests of “fighting Canfield,” and skilled shooting in Crokinole, imported to the lake by a French-Canadian lumberjack.

But the ultimate in entertainment until New York State environmental laws closed the dump on Big Moose Road was the crowd which gathered on weekend evenings to watch bears like Big Ben here spar with each other, feed on camp scraps, and lounge on discarded mattresses.

And then there was that evening a visitor from New York City renting at Lone Pine Kamps tried to place his young child on the back of a bear for a photo! Yes, this writer was an eyewitness at the scene, three men quickly restraining him.

Epilogue (2000 to the Present)

Finishing a social history of Twitchell Lake and updating it to the present time will remain a task for our children and grandchildren. But a few things can be said here and now, the key word being “change.”

As Dan Conable stated in a recent interview with North Country Public Radio, twentieth century women typically spent the whole summer in camp, their husbands joining the family for holiday weekends. Thus, a whole generation of children grew up together sharing lake activities and forming lifelong friendships.

Today, lifestyles have changed, and we lack physical closeness but hope to restore a good measure of social solidarity via our Twitchell Lake website and through our current in-season (and off-season) activities. And maybe even a good share of lifelong friendships!

Neighbor Day has become a great memory for many, replaced by new events that are building connections and relationships. TLF&GS is now the Twitchell Lake Association, and it continues to fulfill all its important social functions, including two face-to-face meetings per year.

Wilbur and Judy Allen host an all-lake get-together each Fourth of July. Dan and Annie Conable sponsor an annual Poetry Potluck over the Fourth of July weekend, guests competing for the coveted title of “Poet Laureate of Twitchell Lake.” That is then followed by a music-themed event each Labor Day Weekend.

Bob Scherfling was the first to put a motor on his floating dock and take it up and down the lake for an outing, and now a host of floating docks go out to sun and party spring, summer, and fall. Some years ago, camp owners linked six or more docks together for an evening music concert and on another occasion for a lake wedding.

Bob Scherfling was the first to put a motor on his floating dock and take it up and down the lake for an outing, and now a host of floating docks go out to sun and party spring, summer, and fall. Some years ago, camp owners linked six or more docks together for an evening music concert and on another occasion for a lake wedding.

Kathy Napier sponsors a lady’s book club which has grown in popularity, another forum for building solid relationships. And the Big Moose Chapel, Earl Covey’s premier architectural achievement, has in recent years become a spiritual and cultural center for the whole Big Moose area, its website keeping summer residents up to date the year ‘round.

Off-season get-togethers have proliferated, too, with good access by car and snowmobile even in winter. Twitchell camp owner Beth Kellogg runs the Little Fox Hotel, a Big Moose gathering place all year long but most crowded during snowmobiling season. Several Twitchell dock ferries launched just after the ice went out to get a good view of the April 8, 2024, total solar eclipse.

The group pictured here on the dock at the Public Landing was poised to make the annual September hike to Beaver River, where over sixty Twitchell lakers regularly make this six-mile trek, others taking the Stillwater ferry to the remote Hamlet.

New Year’s weekend has attracted a growing number of families for snowmobiling, ice fishing, and campfires on the ice. Then there is the February Fly-in, up to ten seaplanes landing on the ice and gathering a good crowd. Not to mention an annual reunion for Twitchell lakers in upstate New York for much of this 21st Century.

Yes, we are discovering and fostering new ways to experience Twitchell Lake. Aziel LaFave summed it up well in his 1991 talk for Neighbor Day:

“While so much has changed in the last fifty-five years, much has not changed. As you leave the dock and head up the lake, East Mountain comes into view. It is just as beautiful as ever. The shore line has lost little of its pristine beauty. Fifty years from now, it will, in its own way, tug at the heart-strings of the next generation.”

Illustrations, from above: ‘Slap Jack Luncheon’ pictures a Lone Pine lean-to and campfire group, Low Hamilton cooking, from the Allen Family Photo Album (ca 1904); 2. First cabin on Twitchell Lake built by guide Hiram Burke in 1870, photo from the Herben Family Photo Album; 3. Survey marker #4 drilled in solid rock by surveyor Frank Tweedy in 1879 as part of Verplanck Colvin’s Adirondack Survey, and found by this writer with a Twitchell search group in 2021; 4. Henry M. Beach postcard titled “A Model Lumber Camp,” Town of Clifton Museum (ca 1910); 5. Watercolor by Noel Sherry titled “First Train Through Big Moose;” 6. David C. Wood map of Twitchell Lake with lots marked by color for the first seven people who purchased land from Dr. William Seward Webb (1900); 7. Carriage drivers Earl Covey & John Denio with their families posing on the Twitchell Creek Bridge, postcard from the Herben Family Photo Album (1910); 8. Skilton Lodge Boathouse with deer hanging, courtesy of Jay Skilton (1908); 9. “Main Lodge, Twitchell Lake Inn, Big Moose, NY,” postcard courtesy of Charlene Ferullo (ca 1940); 10. Adirondack guides Low Hamilton & Francis Young by an unknown photographer (1903); 11. Photo of Lone Pine Tea Room from the lake, Lowell & MaryAnn Hamilton (March 15, 1914); 12. Irwin camp on Silver Lake with builders Tom Rose & Earl Covey posing with young Bob Irwin (July 1, 1900); 13. “Twitchell Lake Regatta,” published in an unknown paper (August 21, 1916); 14. The iconic Harlequin, courtesy Kurious Minds Klum; 15. “Duchess in Hey Day,” by an unknown photographer; 16. Three Lone Pine female guests posing with the hotel mascot, a donkey named Genevieve, unknown photographer (1920); 17. Crowd attending the dedication of the William Covey Memorial Bridge by an unknown photographer, a picture of William superimposed and an arrow pointing to Norman Sherry (August 8, 1927); 18. The Rev. Nicola Di Stefano who founded Camp Bonafide on Twitchell Lake Road (L) and the camp’s chapel (R); 19. Lois Slayton & Clay Briggs in the doorway to the Slayton boathouse from the Slayton Family Photo Album (August, 1915): 20. Bill Kellogg Memorial Lean-to by an unknown photographer (September, 1987); 21. A bear named Big Ben feeding at the Big Moose Road dump, taken by Brad Clark (ca 1970); and 22. a group that hiked from Twitchell to the Hamlet of Beaver River, by Noel Sherry (September 25, 2021).

Recent Comments