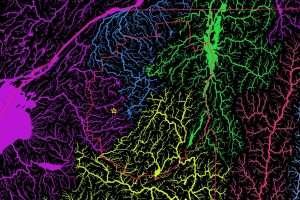

Twitchell Lake is an Adirondack gem that has been protected over time by its remote location. Originally carved out by the last glacier, it drains northwestward into Beaver River, which exits the Adirondacks into Lewis County’s Black River, finally meandering its way into Lake Ontario. Twitchell’s location is starred on this unique watershed map.

Twitchell Lake is an Adirondack gem that has been protected over time by its remote location. Originally carved out by the last glacier, it drains northwestward into Beaver River, which exits the Adirondacks into Lewis County’s Black River, finally meandering its way into Lake Ontario. Twitchell’s location is starred on this unique watershed map.

Twitchell’s history dawned with summer visits to its shores by Indigenous People. While no obvious traces of these visits remain, Bill Marleau mentioned two arrowheads discovered on a family picnic atop a Cascade Lake ridge several miles to Twitchell’s southeast. Cornell University experts dated these to the Woodland Indian period, 820 to 1670 AD.

The Oswego tribal members who left them were probably pausing on a fishing and hunting expedition midway between two important trails — one running along the Beaver River six miles to the north, the other following the Fulton Chain of Lakes six miles to the south.

Early Land Purchase Brings Survey Team Close to Twitchell Lake (1771-1776)

In 1771 a European surveyor by the name of Ebenezer Jessup “missed” the northern shore of Twitchell Lake by less than a mile, marking out the western border to one of the earliest land deals in the Adirondacks. A group of land speculators joined Ebenezer and his brother Edward to purchase over a million acres of wilderness from the Mohawk and Caughnawaga people.

The transaction was fronted through two city of New York shipwrights, Joseph Totten and Stephen Crossfield, with the approval of the English crown. Known henceforth as the Totten & Crossfield Purchase, that boundary line would later provide a possible clue to how Twitchell received its name.

Prior to approving these Totten & Crossfield land grants, an Albany surveyor named Archibald Campbell re-surveyed that same Totten & Crossfield line in 1772, accompanied by eight Native American guides. He rated land quality for anticipated agricultural sale and use. Marking a spruce tree at the corner of Townships 41 and 42, very close to what is now East Pond, Campbell recorded in his field book, “Beach, Maple & Spruce Timber and not Stony… Good Land.”

Loyal to the British Crown, the Jessup’s fled to Canada after the Revolutionary War, Totten & Crossfield land ownership reverting to New York State. Many of its Townships went back up for sale to new buyers after 1779. Twitchell is starred on this map of the Totten & Crossfield inside the Adirondack Park‘s Blue Line.

Loyal to the British Crown, the Jessup’s fled to Canada after the Revolutionary War, Totten & Crossfield land ownership reverting to New York State. Many of its Townships went back up for sale to new buyers after 1779. Twitchell is starred on this map of the Totten & Crossfield inside the Adirondack Park‘s Blue Line.

Township 41 was purchased in 1772 by land speculator by the name of Alexander Macomb. A large part of Township 42 was sold in 1855 to the Sackets Harbor & Saratoga Railroad.

Revolutionary War Era Land Speculation (1776-1798)

Heavily burdened by Revolutionary War debt, New York State put the rest of its “northern wastelands” up for sale, attracting new buyers. Included under that unflattering description, Twitchell Lake ownership passed through four deeds transacted in the city of New York, still without one visit from a European.

Alexander Macomb purchased 3.6 million acres in 1791. As part of Macomb’s Purchase, Twitchell changed hands twice in 1792, William Constable and Samuel Ward its short-term owners. The lake was included in James Greenleaf’s 210,000-acre purchase from Macomb in 1794.

And then in 1798, John Brown took over ownership of the same acreage from Greenleaf. A noted Revolutionary War patriot from Providence, RI, Brown acquired this tract when his son-in-law John Francis was talked into the speculative land deal by Greenleaf, while he was in NYC on business assignment for his father-in-law.

Another purchase of over 200,000 acres in Lewis County, bordering the Adirondacks, was made in 1792 by a group of refugees fleeing the French Revolution.

The settlement was named “Castorland,” French for “Land of the Beaver” and a literal translation of the old Indigenous name for the area, “Couch-sach-ra-ga.” The 442-page Castorland Journal documents early visits along the Beaver River and north of Twitchell Lake. It is just possible the first European visitor to the shore of Twitchell Lake was a French emigre.

Lewis County Settlement & Early Adirondack Exploration (1798-1833)

The next thirty-five years (1798 to 1833) would mark Lewis County settlement with its role in the earliest European exploration of the Adirondacks. This time frame would see the first trail cut into Twitchell Lake by a trapper or guide, with the lake’s name derived from a pioneering Lewis County family.

The State of New York was still under the mistaken impression the Adirondacks could be farmed, but Lewis County to its west was prime agricultural land. The Black River was fed by mountain watersheds — the Beaver, Independence, and Moose Rivers all flowing via the Black River into Lake Ontario.

One person who responded to land incentives published widely by agents in the northeast was Urial Adam Twitchell. Moving from Holliston, MA, in 1802, he established the first general store in a village he helped to name, “Copenhagen” in the town of Denmark, NY.

One person who responded to land incentives published widely by agents in the northeast was Urial Adam Twitchell. Moving from Holliston, MA, in 1802, he established the first general store in a village he helped to name, “Copenhagen” in the town of Denmark, NY.

One of Urial’s accomplishments prior to the War of 1812 was to help survey and build a road connecting Fort Stanwix in Rome with Sackets Harbor on the shore of Lake Ontario.

He married another pioneer named Ruth Wright in 1804, and together they raised their family beside the Deer River just south of Copenhagen. Their children Urial Adam, Jr., Erastus Eames, and Charlotte Mariah added homes to the family compound and made their living as dairy farmers.

John Brown tried to make good on his Adirondack investment with a survey, settlement attempts, and road access through Remsen to the locations he selected for development.

He commissioned three surveyors in 1799 to divide his tract into eight townships, Twitchell Lake situated on the eastern edge of Township Eight. Nicknamed “Regularity,” this Township bordered Townships 41 and 42 of the Totten & Crossfield Purchase (starred on this 1803 map). “Middle Settlement” was in Township 1, a second settlement in Township 7 where iron ore was mined and smelted, hence its name, “Old Forge.”

These two settlements hosted a visit by America’s foremost engineer and inventor of the steamboat, Robert Fulton, commissioned by the NYS Legislature to run a canal through the central Adirondacks, using the eight lakes that became “the Fulton Chain.”

Old Forge was located on the shore of the First Lake in the Chain. This canal scheme would have spurred radical development which would have changed the character of Brown’s Tract (and Twitchell) forever.e

John Brown died in 1803, granting his newly formed townships to his wife and children; Township 8 was willed to James Brown. There was still with no recorded visit to any of Township 8’s beautiful and remote lakes.

Township 7 went to grandson John Brown Francis who was to be elected as governor of Rhode Island in 1833. A frequent visitor to Old Forge, Francis became frustrated as pioneers abandoned their farms due to the short growing season, severe winters, and extreme isolation.

In 1822, Francis made one final attempt at settlement on northern Township 4, where the Beaver River exited the Adirondacks. Clearing 2,000 acres of farmland and connecting No. 4 by road to Lowville, he offered a free farm to the first ten applicants. A school, church, and sawmill were built and by 1835 the hamlet boasted 75 souls, Lake Francis and Beaver Lake gracing the settlement.

The prospect of building a road through what was mostly wilderness 73 miles east to Lake Champlain held out great promise for development.

The NYS Legislature directed Lewis County Commissioners to capitalize on abundant resources nearby, including hydraulic waterpower, valuable soft and hardwood timber, and agricultural land “well adapted to the culture of rye, Indian corn, spring wheat, peas, oats, flax, potatoes & turnips, & all kinds of grasses.” Adventurous trappers and hunters were already collecting bounties on wolves and mountain lions killed along the Beaver River.

Lewis County historian W. Hudson Stephens dated the first fishing party along that rough wilderness route to 1818 or 1819, six prominent county leaders camping at Beaver Falls “with Thomas Puffer as guide.” On the last day of their memorable camping trip, they named one branch of the Beaver “Sunday River.”

Another group called “The Racket Lake Expedition” followed the Moose River up into “the Great North Woods,” reporting on a large herd of moose and boasting a catch of 30-pound trout at Raquette Lake, along with the discovery “of extensive beds of lead and iron ore.”

And then five of William Constable’s grandchildren made regular visits to Raquette and Blue Mountain Lakes from their home in Constableville, following the Fulton Chain and the Beaver River routes into the wilderness.

And then five of William Constable’s grandchildren made regular visits to Raquette and Blue Mountain Lakes from their home in Constableville, following the Fulton Chain and the Beaver River routes into the wilderness.

Stephens mentioned a Constable shanty at No. 4, an 1833 camp-out on Raquette Lake’s “Constable Point,” and the names of the Constable ladies and their friends carved on a “Notched Tree” atop Moumt Emmons. This was an early name for Blue Mountain, 80 miles from Lowville.

John Constable, one member of this family, became a noted Adirondack guide, hanging the rack of a large moose he shot in a tree located in what became the hamlet of Big Moose.

While No. 4 still lacked a road connection to Lake Champlain in 1833, this Beaver River route clearly had become a very well-worn trail frequented by early Adirondack explorers.

The first of three trails to Twitchell Lake branching off this route can be dated to the late 1820s or early 1830s, extending about six miles southeasterly past Wood’s Lake to the northwestern shore of Twitchell (marked on this 1881 map).

This trail was cut by an unknown explorer — John Constable, Thomas Puffer, and No. 4 trapper and guide Orrin Fenton, three candidates. If the trek from No. 4 up the Beaver River was difficult, this trail into Twitchell was extraordinarily rugged, guaranteeing its first European visitors a “wilderness” setting.

Which brings up the key question of when and how Twitchell Lake was named. “Twitchell” does not show up in public records until 1841, but it is highly likely the naming happened much earlier.

Eighteen sixteen would not be too early, the date a prominent judge and surveyor by the name of John Richards was commissioned to survey Township 42 of the Totten & Crossfield Purchase, for partition into 121 Lots. Richards also surveyed the northern road connecting Essex County with the Black River, terminating not far from Copenhagen, NY.

If Urial Twitchell can be placed on a survey crew running the chain along that western Totten & Crossfield boundary line, it could explain how the lake received this name.

Curiously, the mountain between Twitchell Lake and East Pond, crossed by that Totten & Crossfield line, was originally designated in early surveys as “Twitchell Mountain,” not the “East Mountain” of current maps. There is some precedence for a surveyor like Richards honoring a crew member by naming a mountain or a lake for a star employee.

Another survey that passed down this same line near Twitchell was the re-survey of Brown’s Tract, Township 8, sharing that Totten & Crossfield boundary line. Lewis County history buff Charles Snyder identified three surveyors, John Allen, Arnold Smith, and Elkanah French, executing this in 1805. e

It is most likely Twitchell Lake received its name in connection with one of these early surveys.

Cross-Adirondack Road Set Stage for First Wave of Sports Tourists (1833-1860)

Cross-Adirondack Road Set Stage for First Wave of Sports Tourists (1833-1860)

The “dream” of a cross-Adirondack road from Lewis County to Lake Champlain finally became a reality, opening up the Beaver River basin to a first wave of sports tourists, the hamlet of Number Four as the “doorway” for this new traffic.

By 1840, all but one family abandoned No. 4, for the same reasons the other two settlements failed. The Adirondacks were not a friendly environment for farmers. Orrin Fenton and his wife were the only remaining settlers, dropping farming for a new vocation – opening a hotel hosting sportsmen (and women) attracted by early fishing and hunting reports. This 1857 map highlights the Fenton’s with two more settlers who joined in on this new wave of sports tourism.

Nelson Beach, prominent Lewis County lawyer and former No. 4 land-agent, was commissioned by the State of New York to survey the best route for what became the Carthage and Champlain Road.

His 1841 diary featured the first geographical mention of the Copenhagen Twitchell’s, with five references to the tributary where “Twitchel Creek” entered the Beaver River. A log shanty was constructed at that confluence for Beach’s survey crew and a shadowy hermit named David Smith volunteered his boat for river crossings. Squatting on Beaver Lake as early as 1815, Smith had moved upstream and built a shanty where the Beaver’s “stillwater” began, just north of that confluence.

After completion of that road in 1845, another Beaver River hermit named “Jimmy” O’Kane squatted in that shanty, putting up artists Jervis McEntee and Joseph Tubby as they traveled the Carthage and Champlain Road on their well-known 1851 summer sketching tour. The McEntee tour has been documented by Ed Pitts, Adirondack historian and author of Beaver River Country.

Orrin’s two sons, Charles and George, are credited with naming Terror Lake five miles to Twitchell’s north. In the late fall of 1844, they laid out a line of marten traps near Oswego Pond. An intense multi-day storm closed in and sent them north in search of the Carthage and Champlain Road.

Barely surviving the cold and wet, they stumbled on an unknown lake which they named “Terror,” in memory of that terrifying trek. Finally, they did reach the road and make it home to No. 4. Today Terror Lake is 5 miles from Twitchell’s north shore.

Typical of this era was the 1852 news “short” about Lowville lawyer L. C. Davenport’s trip to Beaches Lake, now Brandreth, bragging about a catch of a salmon trout weighing over 23 pounds. The other prime fishing and hunting destinations before reaching Raquette Lake were Smith Lake (now Lake Lila) and Albany Lake (now Nehasane).

Travel accounts for parties that braved the new Carthage to Champlain Road route via horse and buggy appeared in key northeastern newspapers. An 1847 series of five articles by the title “The Wilds of New York” took the reader on a wild adventure from Carthage to Lake Champlain and back, guided by William Higbie. With this new influx of adventurers, guiding ranks grew.

One guide who would soon play a special role at Twitchell Lake was Chauncey Smith. A transplant from Cromwell, CT, he sold his Lewis County farm in 1851 and moved his family into a log home in the abandoned settlement of Number Four near the Fenton hotel.

Hunting and trapping had clearly become his passion, with extra income earned through fox, wolf, and panther bounties. He thus joined the emerging craft of wilderness guides with storied names like Thomas Puffer, Orrin Fenton, John Constable, William Higbie, Amos Spofford, and Arettus Wetmore.

In August 1858, Spofford guided a group of Lowville notables that included an editor, pastor, historian, lawyer, and professor on a three-week trip to “Racket Lake and Blue Mountain.” Chauncey’s sons, Marcus and Charles, joined the guiding profession, too, with four of his sons-in-law also expanding the family business.

A journey into “Hunter’s” or “Fisherman’s Paradise” was not a one day or weekend affair. It meant a two-to-three-week marathon in the wilderness. Provisioning and guiding services were available in Lowville and at Number Four.

A journey into “Hunter’s” or “Fisherman’s Paradise” was not a one day or weekend affair. It meant a two-to-three-week marathon in the wilderness. Provisioning and guiding services were available in Lowville and at Number Four.

To accommodate the influx of sports tourists, several new structures were built along the Carthage to Champlain Road. Edwin Wallace, editor of the annual Descriptive Guide to the Adirondacks, described two of these in detail.

The first was called “Rock Shanty” because it stood by the side of an immense rock just fifty feet east of that first trailhead for Twitchell Lake. Wallace named four hunters from Oswego County as “the builders and architects” of this overnight stop on the Carthage to Champlain Road. Orville Bailey, Briggs Wightman, Lewis Diefendorf, and Orlando Reynolds completed their building project in the summer of 1856.

Two summers’ later three members of this Oswego party “assisted Uncle Chauncey Smith in rearing his woodland structure at South Branch.” Chauncey’s “Elk Horn Shanty” had attached stables for horses. It is marked in blue on this 1879 W. W. Ely map at the convergence of Beaver River with its South Branch, almost 20 miles east of his homestead at Number Four, marked in purple.

Also depicted is a second access route to Twitchell Lake from the Carthage to Champlain Road, a “Horse and Wagon Road” put in around 1848 after that Road was completed. According to Wallace, it extended to Big Moose Lake, possibly creating the first link between these two bodies of water. In an 1864 letter to his son George, Chauncey revealed just how busy this wilderness outpost had become:

“I have spent the most part of my time up at my forest house through the summer and winter up to the first of Jan, waiting on gentlemen sportsmen and hunters and doing something at hunting myself … I have had 25 customers in one night … and 3 ladies … I had 10 hunters there for a month or more the fore part of this winter … Besides goers and comers, venison and fur buyers”

Twitchell Lake changed hands twice in this time-frame, all of John Brown’s heirs selling their shares in the tract to John Brown Francis by 1840. James Brown’s deed for Township 8 and Twitchell Lake, was part of that transfer.

In 1850, Francis turned around and sold all his Brown’s Tract holdings to Lyman R. Lyon of Lyons Falls, Lewis County’s representative to the State Assembly in Albany. Lyon was engaged in the lumber and tannery industries, and this large wilderness tract would provide abundant new sources for virgin timber, not to mention its mining possibilities.

One of his survey maps located “Lyon’s Rock” on the banks of Twitchell Creek near where the O’Kane shanty once stood, now submerged by Stillwater Reservoir. It marked an important boundary and was signed “L. R. Lyon.”

Lewis County newspapers used the phrase “Melancholy Occurrence” for tragic events that visited the region. One of those events occurred at Twitchell Lake in 1856. The article that reported it printed the second public mention of Twitchell that has been found, this one not as a creek but as a lake.

Orville Bailey and Briggs Wightman traveled from Oswego to Rock Shanty for their late fall hunting trip. Orville was too sick to venture out. Briggs departed for the trail to Twitchell Lake to set out his hunting traps, promising to return with fresh trout.

When three days passed without a word, Orville was beyond concerned. Traveling back from Raquette Lake, guide Amos Spofford stopped in and agreed to hike to Twitchell in search of Briggs. Enlisting three men to help, including guide Marcus Smith, he arrived at the shore and spotted a hat and rifle beside a hole in the ice.

When three days passed without a word, Orville was beyond concerned. Traveling back from Raquette Lake, guide Amos Spofford stopped in and agreed to hike to Twitchell in search of Briggs. Enlisting three men to help, including guide Marcus Smith, he arrived at the shore and spotted a hat and rifle beside a hole in the ice.

Using a raft, they fished the body out but lacked the manpower to carry him out. Returning with “eight sturdy hunters,” they delivered the body to the C-C Road for transport to the coroner in Lowville. Howling wolves forced them to suspend the body under water until the final rescue.

Rounding up eight hunters in late November 1856 indicates just how busy the Carthage to Champlain Road was becoming. The source of the Beaver River lay upstream at Smith Lake, where its namesake David Smith had relocated his hermit’s shanty ca 1830, before disappearing in 1840.

Many of the adventurers on that road preferred the more distant locations of Raquette, Beach, Blue Mountain, and Long Lakes, with an overnight stay at Elk Horn Shanty. Twitchell Lake was still very remote from these prime fishing and hunting grounds, but that was all about to change.

A Second Wave of Sports Tourism Became a Flood (1860-1889)

This next era saw Twitchell Lake ownership shift again, this time on deeds belonging to two railroading companies committed by an 1848 Charter to open the Adirondack wilderness to rail service.

Adirondack waterpower, lumbering, and mining potential led to lively debates in Albany, where the Legislature granted the Sackets Harbor and Saratoga Railroad Company this Charter, with land purchase for its right-of-way at the bargain price of five cents per acre.

One of those transactions came in 1855 with the company purchase of all the lots marked in red on this map of Totten & Crossfield Township 42, East Pond in its SW corner and Twitchell just over the mountain to the west.

This railroad route was surveyed by Squires H. Snell as one potential route for a track through this township, up to and paralleling the Carthage to Champlain Road, and on to Sackets Harbor.

There are manifold reasons why this well-vetted project failed, but it does not take much imagination to realize how such a nearby rail line would have altered Twitchell history.

In 1860 this railroad was reorganized as “The Adirondac Estate and Railroad Company.” Lyman Lyons sold this new company the balance of his Brown’s Tract land, without one track being laid. The year 1863 would see the Charter and deed (with Twitchell Lake) passed to “The Adirondack Company,” Union Pacific Railroad’s Thomas C. Durant at the helm.

By 1871 a track was laid by this new corporation from Saratoga Springs to North River, but no further. Lewis County residents were nonplussed: “This part of the State has been so often humbugged with abortive railroad projects, that we would advise our friends not to go into ecstasies on the subject yet awhile.” That would hold true until 1892.

While all this wheeling and dealing was going on, sports tourism in the Adirondacks entered a second wave. Places like Albany and Smith Lakes were getting so crowded seasonally that guides were now taking their sports on side trails to places like Twitchell Lake and the Red Horse Chain of Lakes. Paul Crouch & Beatrice Noble’s Twitchell & Thereabouts referred to one party that probably visited Twitchell Lake multiple times in this era:

“The late Mrs. Albert P. Fowler of Syracuse believed she and her mother, Mrs. Irving Vann, were the first white women to visit Twitchell, in 1880, staying at what was known as ‘The Syracuse camp’ which I gather to have been about where Francis Young’s camp was, at the foot of East Hill.”

After vacation trips to areas like Brown’s Tract, pastors in Boston and the city of New York preached and lectured on “the hunting and piscatorial sports that are to be enjoyed in this famous mountain region… the extensive forests, the lofty mountain peaks, and the placid lakes.”

Many of the newcomers who responded to glowing reports like this were not prepared for the rigors of a place that one reporter called “punkeydon,” for its pesky biting insects.

Of all the guides in the Beaver River basin, Chauncey Smith & family were best suited to handle the increased traffic. In 1864 Chauncy published the following ad for his guiding business after two guides married into his family – Losee Lewis to his daughter Anna (1855) and Arettus Wetmore to Maryett (1857):

From each of the above (Losee, Arettus, and Chauncey), home entertainment, guides, keep of teams, boats, fishing tackle, guns, traps, etc., etc., are obtainable. Livery, for freight and parties, into, from, and beyond No. 4, at reasonable rates, on notification, by mail, P.O. Address of either: Watson, Lewis County, N.Y.

Then in 1867 two more guides joined the family — James Lewis marrying Maryett (after Aretus died), and Hiram Burke wedded to daughter Ursula, that same year. The names of James and Hiram show up frequently thereafter in news shorts, guiding fishing and hunting parties into Twitchell Lake.

It is probable Chauncey enlisted them after 1867 to help cut a wagon road directly to Twitchell Lake from his Elk Horn Shanty, a third access to remote Twitchell Lake.

The picture here shows the first structure on Twitchell’s shore, built by Hiram Burke in 1870. There is an interesting back-story to this log shanty that may connect this building project with Urial Twitchell’s grandson, Charles Erastus Twitchell.

Charles was a drummer in Copenhagen’s famed cornet band, which played for a Christmas eve program in the Losee Lewis Hotel in Watson in 1869. Watson borders Number Four. Edwin Wallace later made this curious observation in his Guide to the Adirondacks, regarding the naming of Twitchell:

“It received its unpoetic title from a settler, rejoicing in that name, who once made a clearing near by… Hiram Burke, (P. O. Lowville), the very efficient guide, has erected a substantial hunting lodge on the N. shore of Twitchell L., where sportsmen are entertained and furnished with the best fare that the forest affords.”

Admittedly, this is guesswork, but the only clearing of logs at Twitchell in summer 1870 was for the Hiram Burke shanty. And it seems logical to reason that a settler who “rejoiced in that name,” would have had to be a Twitchell.

That Christmas eve event could well have led to the project Wallace was referring to. Twitchell Lake and Creek were named years before this. But Burke’s Christmas eve curiosity about this drummer’s name with his grandfather’s connection to Twitchell Lake could well have provided the opportunity for inspiring this 1870 summer project.

Wallace then continued his description of Burke as Twitchell Lake’s guide:

Wallace then continued his description of Burke as Twitchell Lake’s guide:

“When desired, he will conduct his guests (no better woodsman than he) to the various choice sporting grounds which lie in the neighborhood. In the immediate vicinity, in different directions, are twelve or fifteen tiny ponds, usually swarming with large trout, and gleaming like gems in their solitary fastnesses amid the deep green of the forest. These include Silver, Oswego, Arthur, East, Mud, Marenus, Hackmetack and Twitchellette.”

Twitchell is in fact surrounded by 12 to 15 small ponds, three listed by Wallace the same as today (East Pond, Silver Lake, and Oswego Pond). “Twitchellette” most likely refers to Little Birch Pond, the smallest and closest; “Hackmatack” (a term for the Tamarack tree) could match Lilypad Pond; and “Mud Pond,” probably is today’s South Pond.

The last two ponds mentioned here are “Marenus” (Jock Pond?) and “Arthur” (Razorback Pond?). It turns out Marenus and Arthur were two of Burke’s repeat customers, as illustrated in this Journal & Republican news clip from May 11, 1882.

The last two ponds mentioned here are “Marenus” (Jock Pond?) and “Arthur” (Razorback Pond?). It turns out Marenus and Arthur were two of Burke’s repeat customers, as illustrated in this Journal & Republican news clip from May 11, 1882.

C. S. Marenus was Lewis County’s DA, Eugene B. Arthur a Lowville attorney and hardware store owner. Edwin Wallace, an early guest in Chauncey’s Elk Horn Shanty, preserved these acts of naming by Hiram Burke, because he had come to view Hiram as Twitchell Lake’s patron guide.

John C. Wright, Mystery Writer

The rough log shanties and lean-tos that Adirondack guides constructed in this early era were not located on property that had been surveyed and prescribed in a deed. These guides were squatters who knew their absentee landlords would not come after them. By that understanding, they typically claimed a favorite body of water for their fishing and hunting parties, supplied with some form of shelter and a guide boat with oars.

Etiquette meant permission was needed to use another guide’s shelter, but it is safe to assume that the Hiram Burke shanty had regular use for the fishing and hunting seasons as this second wave of sports flooded in through Number Four.

One of the most interesting groups to occupy the shanty at Twitchell Lake reported on their nine-day trip in a long article in Lowville’s Journal & Republican published on July 8, 1874.

Titled “North Woods,” the mystery writer introduced his party as John the writer, Alexander the tooth puller, Charles our literary man, Amos the farmer, the Major, Eleazer the gentleman, and David his brother. Hours of research on clues provided by “John the writer” finally revealed the identities of these important visitors from Lowville and Copenhagen, NY.

A rough horse and buggy ride brought them to No. 4’s Fenton House for an overnight, then to Wardwell’s, a new “Hotel” on the Carthage to Champlain Road by the Twitchell Creek crossing. Leaving there on foot, they crossed the Creek and soon turned south toward Twitchell just before Rock Shanty.

They “tramped” to Wood’s Lake for an overnight, then on to Twitchell, describing their arrival at the Burke shanty in glowing literary terms:

“A day and a half baiting here [at Wood’s Lake], fishing and resting, and we started for Twitchell’s Lake, five miles farther on over mountain and glen, which was really the objective point of our trip. There we expected to find rest from our labors, fish in abundance, together with all that quietude and repose that one ever imagines can be found amid “Solitude’s Mystic Wilds.” A few hours tramp brought us in full view of the placid water, and nearby, up a little elevation or cliff, stood our humble dwelling, quiet and cozy as solitude’s own ‘sybil great.’”

“A day and a half baiting here [at Wood’s Lake], fishing and resting, and we started for Twitchell’s Lake, five miles farther on over mountain and glen, which was really the objective point of our trip. There we expected to find rest from our labors, fish in abundance, together with all that quietude and repose that one ever imagines can be found amid “Solitude’s Mystic Wilds.” A few hours tramp brought us in full view of the placid water, and nearby, up a little elevation or cliff, stood our humble dwelling, quiet and cozy as solitude’s own ‘sybil great.’”

The author of the article borrowed from an 18th Century English poet, whose “Ode to Solitude” praised the virtues of Repose and Friendship against the vices of Pretense, Corruption, and Dissention so common in his day.

John “the writer” also quoted from other sources, including William Cowper’s anti-slavery poem, “Timepiece.” Extensive detective work revealed him to be John C. Wright, President of the Lewis County Teacher’s Association, Lowville Academy teacher, and Supervisor for the town of Denmark.

“Tooth puller” turned out to be Dr. Will Alexander, Copenhagen’s dentist. “Literary Man” was Charles Chickering, Copenhagen hardware store owner, “the Farmer” his brother Amos Chickering, an agricultural leader.

“The Major” was none other than Lewis County’s Coroner, Sanford Coe. And “the Gentleman” with his brother were Eleazer and David Spencer, who together ran a business as “Stump & Rock Pullers.” Curiously, news clips recording Twitchell Lake sporting trips for this era named many of the sportsmen as Copenhagen residents.

What is most remarkable is that two members of this fishing party were related by marriage to Charles Twitchell. This 1857 map of Lewis County captures the Twitchell family compound south of Copenhagen’s center, the arrows pointing to the homes of Charles’ father Erastus Eames (E. E.), his uncle Urial Adam (U. A.), and his first cousin Jerome (Jer.).

The star on this map points to the Twitchell’s next-door neighbor, John C. Wright. John “the writer” Wright must have known the story behind the naming of “Twitchell’s Lake.” His choice of Twitchell for an annual fishing trip was certainly not coincidental.

Verplanck Colvin, Famous Mapmaker

Verplanck Colvin spent three summers in the Adirondacks, becoming interested in its topography, geology, and preservation. He gained the attention of state officials when a paper he wrote was read at the Albany Institute, tying clear-cutting of Adirondack forests with reduced water flow in the State’s canals and rivers.

In 1872, he was named to a newly created post as Superintendent of the Adirondack Survey. The NYS Legislature approved a $1000 annual budget for the creation of an accurate map of the whole region. He began with the high peaks and a precise measurement of Mount Marcy’s altitude.

In 1876 he set up camp on Fourth Lake, determined to plot old boundary lines on his emerging map and to check in with his Beaver River surveyors, Squire Snell and Frank Tweedy. Legendary guides Jack Sheppard and Alvah Dunning led the party across “Great Moose Lake” (Big Moose Lake), following an old trapping-line trail to Twitchell Lake.

In 1876 he set up camp on Fourth Lake, determined to plot old boundary lines on his emerging map and to check in with his Beaver River surveyors, Squire Snell and Frank Tweedy. Legendary guides Jack Sheppard and Alvah Dunning led the party across “Great Moose Lake” (Big Moose Lake), following an old trapping-line trail to Twitchell Lake.

On October 15, they discovered a new body of water, naming it “Hackmatack Pond” for its many Tamarack trees (now Lilypad Pond). Rounding the north end of Twitchell where they stationed a survey stadium pole, the party made “the long weary march” to Beaver River, the old trail blocked by huge swaths of fallen timber due to beetle infestation and “furious hurricanes.”

The party was back on the 19th for an overnight in “Twitchell Lake Camp” (Burke’s shanty). In his journal, Colvin declared Sunday the 20th to be “Survey day.” Hiking the length of Twitchell’s western shore, he sent his guides across to the opposite side to hold up stadia poles for three distance measurements read off his “micrometer telescope.”

Colvin’s “reconnaissance map” of Twitchell, shown here, pinpoints those locations — the first one by the island, the second by the old inn, and the third by the Sherry camp. Stationing another stadium pole on the southern end of the lake, Colvin rounded the bend, crossed the outlet, and took two more measurements to both ends of the lake, standing on “the Big Rock” in front of Chris Hall’s camp.

The topographically accurate map next to Colvin’s here shows his measurements to be fairly accurate, the length readings at a 2 to 8% variance, the width measurements varying by 0.1 to 14%. If Colvin had simply marked the northern 39° line as NE instead of NW, he would have sketched an accurate profile for the lake rather than this odd kidney-shape.

Interestingly, Colvin identified the Big Rock as made up of “hornblende in syenite with feldspar present,” taking a sample for his rock collection. A brass marker on Big Rock now commemorates this famous surveyor’s visit to Twitchell Lake.

Colvin’s reputation as a nature writer rings true in this journal entry as the crew departed for Big Moose Lake to finish survey work there before returning to their Fourth Lake headquarters, and home to Albany:

“Passed westward to the outlet — which proves to be a most beautiful spot — for here the lake pours from its very edge out over a fall of 8 or 10 feet to form a picturesque stream margined with bright green moors — from dead timber &c &c (Vol. 270, pp. 28-9)”

The beauty of the Lake’s outlet into Twitchell Creek with its trout pools is famous for camp owners and lake visitors alike. But as Bill Marleau pointed out in Big Moose Station, Colvin missed the most beautiful spot not too many yards downstream, where a glacial erratic the size of a two-story house sits atop a 40 to 50-foot sheer drop of falls, boulders, and trout pools.

Frank Tweedy, Surveyor & Botanist

The Tweedy family summered in the hamlet of Number Four where Frank collected his first plant specimen along the shore of Beaver Lake. Trained as a civil engineer, he was hired right out of college by Verplanck Colvin, who employed him for the summers of 1876 through 1879 in the Western Division of his Adirondack Survey.

Commanding a crew of “flag and chainmen, choppers, guides and packmen, ten all told,” Tweedy surveyed and mapped the Beaver River basin from Lowville to Saranac Lake and the Totten & Crossfield line from “The Great Corner” south to Seventh Lake.

Commanding a crew of “flag and chainmen, choppers, guides and packmen, ten all told,” Tweedy surveyed and mapped the Beaver River basin from Lowville to Saranac Lake and the Totten & Crossfield line from “The Great Corner” south to Seventh Lake.

Of the six Beaver River maps Tweedy produced, this portion by the Totten & Crossfield border-crossing brought expert detail to an important river system that was just a dotted line on older maps. Noted on the Totten & Crossfield line are crossings of the old bed of the Sackets Harbor & Saratoga RR and the Champlain Road.

The wagon trail from Chauncy Smith’s old shanty at South Branch to Twitchell, the old bed of the Beaver River, with its many bends and frequent rapids, are also noted. His other maps of Beaver River label wide areas as “Old Burning,” referring to a 25-year-old forest fire.

Survey flags on this map marked the river crossing which ended Tweedy’s 1878 season, capped by a notable highlight. He had accompanied Colvin 12.7 miles north along that rugged Totten & Crossfield line to share in one of the greatest moments of his bosses’ career, discovery and restoration of “the Great Corner.” That landmark legally anchored much of northern NY, including St. Lawrence,

Herkimer, Hamilton, and Lewis Counties. Colvin’s description of that event, with his famous sketch of the scene, is historic and exciting!

Herkimer, Hamilton, and Lewis Counties. Colvin’s description of that event, with his famous sketch of the scene, is historic and exciting!

Another highlight capped Tweedy’s 1877 season. Two methods for producing an accurate map were then available, networking mountain peaks for altitude, angle, and location, and the more laborious running of the 66-foot Gunter’s Chain through swamp and woodland.

Few mountain peaks with wide views meant most of Tweedy’s work involved running a line of chains, the Totten & Crossfield angle a constant slope of South 28° East. On October 26, Tweedy met the Eastern Division survey party near Lower Saranac Lake, “closing the long line from the shore of Lake Champlain at Westport to the clearings at Fenton’s in Lewis County, on the western side of the wilderness,” an event celebrated by all of Colvin’s crew.

Tweedy’s last survey season (1879) put him at Twitchell Lake with a base of operations out of Hiram Burke’s shanty. He completed two survey journals that season — one in narrative format with 25 mentions of Twitchell Lake, the other one plotting his 12-mile “course of stations” along the Totten & Crossfield line from Beaver River to Seventh Lake, with sketches of the terrain next to each table of stations.

Several Stations are noted on the accompanying illustration of Tweedy’s Journal, Station 340 an Offset Line to Twitchell Lake, Station 344 marking “Twitchell Mountain,” and Station 364 — a 548-foot Offset Line on the left side of the T&C line. Offsets were perpendicular lines extending to important features that needed to be accurately placed on a final map. Tweedy’s progress on the survey line was typically a half mile per day.

Tweedy’s narrative journal includes this sketch of Twitchell’s north bay, less than a mile from Station 340 on the perpendicular Offset Line. He labeled it “Lizard Bay” for some unknown reason, angles and measurements marked to pine trees and points on the bay.

The important corner for Townships 42 and 41 of the Totten & Crossfield Purchase was located at Station 390 on the other side of a small stream that ran into East Pond. Tweedy took a day and a half to drill and set a benchmark in solid rock, under a pile of stones holding up a spruce pole.

This was the fourth of five important benchmark’s he installed on that 24-mile line. In the summer of 2022, Twitchell residents led by Noel Sherry found that B.M., and restored it. At 50 feet between Stations, it lay precisely 1,300 feet beyond the East Pond Off-set.

It is fascinating to see the Burke shanty as a busy hub in 1879, James Lewis’ horse, one means of transport for mail and supplies between this outpost and the outside world. In his journal, Tweedy mentioned a weekly trip to Number Four to exchange letters with his boss, catch up on paperwork, prepare maps and benchmarks, maintain survey equipment, pay bills, and collect plants. And Tweedy’s autobiography added that standard fare for his survey crew included a breakfast of flapjacks and trout, with venison dinners.

Since Tweedy was using the Burke shanty for much of that season’s prime time — July through October — it is almost certain he had received the guide’s permission. Sports parties for that season would have set up separate camps along the shore. Tweedy does not say so in his journal, but it had to be awkward when Hiram Burke showed up on July 16th at his own Twitchell Lake shanty to arrest Tweedy’s guide: “About 7 AM, H. Burke and the deputy sheriff from Lowville reached our camp to serve a summons on our guide for killing deer.”

According to a Lowville Times bulletin, there were two infractions, hunting deer out of season and “using a gill net for trout at Twitchel Lake.” Burke moonlighted with the Lewis County Sportsman’s Association, guiding the sheriff into this northern wilderness when complaints were filed against sports parties. Best practices for hunting and fishing were in their formation stages, and this Association was the watchdog for abuses in the western Adirondacks.

Frank Tweedy went on to a successful career as a Rocky Mountain surveyor, with a pioneering role at the United States Geological Survey, Washington, DC. His experience in the Adirondacks and at Twitchell Lake launched him on his path as a mapmaker and amateur botanist.

Today, there are over 6,000 plant specimens in herbaria around the US and in Canada collected by Tweedy, 33 of those from the Adirondacks. Utricularia resupinate, popularly known as Northeastern Bladderwort, was collected one Sunday in 1879 along the shore of Twitchell Lake. A handful of these plants actually bear the Tweedy name.

A Movement Birthed

It has been assumed the conservation movement in the Adirondacks, and then in America, arose solely as a reaction to logging industry abuses at the turn of the century (1900).

This top-down view has been challenged, pushing the birth of the movement back to the early 1870s with the grassroots formation of sportsman’s clubs, guiding associations, and national magazines like Forest and Stream, which advocated for local, regional, and State laws to help preserve and renew the stock of fish and game.

This top-down view has been challenged, pushing the birth of the movement back to the early 1870s with the grassroots formation of sportsman’s clubs, guiding associations, and national magazines like Forest and Stream, which advocated for local, regional, and State laws to help preserve and renew the stock of fish and game.

One of the reasons Hiram Burke took his clients to fish and hunt on the smaller ponds surrounding Twitchell was a noted decline in the supply available where his cabin stood. The use of hounds to hunt deer or gillnets to snag trout had depleted a once plentiful season for fish and game. Burke and his guiding family were a significant part of this grassroots movement.

His meagre guiding income was supplemented in several ways. In the winter months he made fur and buckskin gloves he sold to finance his summer trips to Twitchell Lake. He also “packed his fur, venison and other game back through the woods to Lowville,” to sell. But he was clearly a part of the conservation movement as he helped enforce early fish and game laws, as affirmed here by the Lewis County press:

“The Lewis County Sportsman’s Association is active and energetic in its pursuit of violators of the game law. There’s probably not another Association in the State that is doing such good work to prevent the killing of deer out of season as this club; and for it they are entitled not only to thanks, but in the pecuniary assistance of wealthy sportsmen in their noble work.

“A few days since the officers of the association received trustworthy information that a Philadelphia party of four, with two guides, were killing deer at Twitchell lake, F. C. Schraub, Esq., the prosecuting attorney for the club, issued the necessary supreme writs, and the Deputy Sheriff Finch, with guide H. Burke, started on Tuesday morning last with the legal documents and found the ‘deer slayers’ in camp, with a saddle of freshly killed venison hanging out for a sign. He also discovered, in addition, four hides of deer lately killed.”

Before returning home, that Philadelphia party of four had to report to the courthouse in Lowville to pay a substantial fine.

Sold to Railroading and Logging Interests (1889-1899)

Sold to Railroading and Logging Interests (1889-1899)

The ten years leading up to 1900 brought momentous changes to Twitchell Lake as the twin developments of logging and railroading finally reached its shores. Sports tourism increased, too, with news sources in this decade carrying messages like these: “Big Moose country has become a favorite place for sportsmen in the past few years” and “Twitchell Lake [is] probably the surest fishing ground known to man.”

A trail and wagon road from the northwest remained the main access to Twitchell, until Stillwater Reservoir buried the Carthage and Champlain Road with the damming of Beaver River. Access to Twitchell from the southeast increased using a trail from Big Moose Lake and the Carry Trail from the Fulton Chain of Lakes.

The Carry Trail left “Big Moose Landing” on Fourth Lake, passing Rondaxe, Dart’s, and Moss Lakes, before reaching Big Moose Lake. Two “North Woods guides,” Henry H. Covey and James H. Higby, used the Carry Trail in 1891 when they “took a unique trip to Big Moose Lake from Old Forge, on a sled drawn by two dogs.” Covey’s Camp Crag and the Higby Club hosted sports tourists on Big Moose Lake.

Right-of-way was approved in 1887 for telephone lines from Old Forge to Big Moose, and soon to Twitchell, an important connecting link between this wilderness region and the outside world.

Two years later the Fulton Chain Fish Hatchery dug small ponds in the beds of streams near Twitchell and Big Moose Lakes for trout spawning. The Adirondack Guide Association was organized in 1891 with Verplanck Colvin as its honorary president.

Hounding deer and catching trout with gill nets was now strictly prohibited. New Gilded age hotels sprung up on popular lakes to replace the sporting shanties and log camps of “the old days.” By the end of this era, a major survey was completed to partition Twitchell into lots for sale to summer residents and hotel owners.

Three Companies Logging the Beaver River

Three Companies Logging the Beaver River

“Timber gold” in the Big Moose area was some of the last to be harvested in the Adirondacks, given its remote distance from rivers like the Beaver and the Moose. Most desirable by the industry was the white pine and spruce for lumber, the softwood logs floated downstream to mills via spring river drives.

The leather industry prized hemlock, stripping the bark and leaving the wood behind in the forest. Lastly, the paper industry went after hardwood, too heavy to move by river and thus transported after railroad travel was running through the Adirondacks.

The Beaver River was navigable by canal-boat five miles upstream from the mouth of the Black River, where the city of Beaver Falls grew into a major mill center. This illustration depicts “Basselin Landing” in Beaver Falls, the perfect location for commercial lumbering, leather tanning, and paper production to develop.

While Lewis County papers called Watertown “the Lowell of Northern New York,” Beaver Falls was more deserving of this title. Two of its three lumber barons hailed from that Massachusetts mill center, the first one John M. Prince followed by a trio of Isaac Norcross with his colleagues Daniel and Charles Saunders.

New York State declared the Beaver River to be “a public highway” for logging in 1853. One year later, Prince purchased 15,000 acres of virgin timber in Totten & Crossfield’s Township 42 near Twitchell Lake. It is probable that Prince was attracted to the Adirondacks by the promise of a railroad line that would transport his logs to the mill, avoiding seasonal and dangerous river drives.

Interestingly, he sold Chauncy Smith the 50-acre parcel marked on this map, hiring him as caretaker for his forest holdings “to prevent it from being destroyed by fire.” That fork of the Beaver River’s South Branch is where Chauncey built his Elk Horn Shanty. Prince established a number of lumber camps to extract virgin timber from Township 42.

The next “improvement” of the Beaver River came in 1864 when the State spent $5,000 to erect a dam at the outlet of Smith’s Lake for pushing logs down in the spring, blasting rocks and straitening river bends to create better drive channels.

Norcross & Saunders took over the four Prince mills with their timber holdings in 1869, expanding their Beaver Falls operation to a capacity of 30 million board-feet per year. This huge operation added lumber camps along the Beaver River and up tributaries like Twitchell Creek.

In 1872 a new lumberman named Theodore Basselin purchased the Norcross & Saunders mill complex at Beaver Falls with their Beaver River forestland, capitalizing on debarked Hemlock upriver.

By 1889, he was the controlling member of the Adirondack Timber & Mineral Company, a true lumber conglomerate with over 300,000 acres of “virgin pine and spruce, plus hemlock and hardwoods.”

A year later, Basselin incorporated the Beaver River Lumber Company, which immediately purchased 306,000 acres from Durant’s Adirondack Company – a land deal which included Brown’s Tract Township 8, with Twitchell Lake.

Dubbed “Adirondack’s Lumber King,” Basselin’s influence extended all the way to Albany, where he promoted an 1886 State contract to erect a dam on the Beaver River where the Stillwater dam is today, as a guarantee of adequate water for his river drives.

He chaired the Forest Commission formed in 1885 “to protect the forests.” Adirondack historian Barbara McMartin aptly called this “the proverbial placing of a fox as guard to a henhouse.”

Thirty-six years of logging by three major companies pushed lumber camps further and further up Beaver River’s tributaries in pursuit of virgin softwood timber. And when the railroad finally arrived, hardwood was harvested.

Of the two lumber camps near Twitchell Lake, Camp #1 on this map has been dated to the 1880s by items found in the camp dump, including an 1864 penny, clay pipes, cone-shaped ink bottles, glass buttons, horseshoes, logging-sled parts, and an early bottle of Minard’s Liniment dated to about 1885.

Camp #1 was located about a quarter mile up Twitchell Creek from today’s bridge, clearly part of the old system of winter camps, skid roads, and river drives. This map traces the skid or tote-road several miles down Twitchell Creek to the location of the sluice dam, which backed up millions of gallons of water.

Paul Crouch offers a vivid description of this sluice-dam:

“It may seem strange to talk about river drives down Twitchell Creek, but by the use of sluice dams I have seen it done on smaller creeks than that … The sluice dam on Twitchell Creek was about a mile north of Big Moose station and went out only ten or fifteen years ago.

“Without the ten-foot sluice it ponded up a couple of acres; with the sluice gate in place it may have ponded up five to seven. When the time came for the drive, the sluice would be opened and the logs in the pond or on the rollways on the shore would be sent down the resulting torrent.”

Where did this mass of virgin pine and spruce logs go? A select team of “river monkeys” directed the drive 36 miles down to the Basselin mill complex in Beaver Falls, the biggest company in operation at that time.

Henry Beach’s 1910 photo here of a “model lumber camp” captures the collection of buildings (and equipment) present in Lumber Camp #1, complete with men’s bunkhouse, cook’s kitchen quarters, stable, blacksmith shop, bathhouse, storage area, sprinkler, snowplow, and logging sleds.

Henry Beach’s 1910 photo here of a “model lumber camp” captures the collection of buildings (and equipment) present in Lumber Camp #1, complete with men’s bunkhouse, cook’s kitchen quarters, stable, blacksmith shop, bathhouse, storage area, sprinkler, snowplow, and logging sleds.

On a small scale, it was like a town in the woods, populated by a jobber, cook, blacksmith, axemen, swampers, spud crew, skidding crew, scaler, and river monkeys. And while some of these woodsmen spent a Sunday off playing cards, writing letters, smoking a clay pipe, or a fine Havana cigar, others would have ventured up the hill to fish for trout in Twitchell Lake.

My New York Almanack article, “An Adirondack Lumber Camp,” offers a good rundown on what a typical camp day and logging season looked like, with each of its multiple challenges.

Webb’s “Fairytale Railroad”

After 50 years in pursuit of a cross-Adirondack railroad, the dream was finally achieved by a man trained as a medical doctor, William Seward Webb.

The story of the feat workers accomplished in just 18 months is told in a book aptly titled Fairy Tale Railroad. Webb married railroad magnate William H. Vanderbilt’s youngest daughter Lila – against her father’s wishes — later responding to his invitation to join the family railroad business. When the State refused to grant Webb right-of-way for his first railroad project, he dipped into the family fortune to fund it.

Surveyors mapped out a 160-mile route from the Mohawk River to the northern town of Malone, which already had railroad connection with Montreal. Herkimer lawyer Charles E. Snyder was retained to purchase the string of parcels needed for the proposed route, Township 8 with Twitchell Lake purchased in 1891.

Surveyors mapped out a 160-mile route from the Mohawk River to the northern town of Malone, which already had railroad connection with Montreal. Herkimer lawyer Charles E. Snyder was retained to purchase the string of parcels needed for the proposed route, Township 8 with Twitchell Lake purchased in 1891.

Historian Paul Crouch cited a firsthand source for an alternative survey plan that would have threaded the rail route right between Twitchell Lake’s eastern and Big Moose Lake’s western shore, an option that would have radically altered the region’s character. That was abandoned because it would have pushed the track 100 feet higher than the 2,040-foot highpoint just north of Big Moose Station.

Bill Gove in his book Logging Railroads in the Adirondacks, described the dramatic execution of project plans. “Webb’s army” consisted of four thousand Blacke, Indigenous and immigrant workers, distributed in camps all along the line, rapidly carving a 100-foot-wide swath through the forest.

After blasting impeding bedrock, each section employed five “gangs,” as follows: The first gang cleared 50 feet to either side of the survey line of all the trees; the second gang followed immediately behind, piling and burning all the timber in the middle of that path; the third gang came with horse-drawn brush-breaking plows to pull the stumps and burn them on those same fires; the pick-and-shovel men of the fourth gang soon approached to create a level grade, removing high and filling in low spots; and the fifth gang then laid down railroad ties, spiking the rails in place.

The crew laying out railroad ties in this picture gives some idea of the sheer magnitude of the task. Although many workers suffered from pitiful wages sometimes bordering on virtual-slavery, Webb otherwise spared no expense to complete the project as soon as possible, at an estimated cost topping $40,000 per mile.

Finally, on October 12, 1892, about half a mile north of Twitchell Creek Bridge, the two ends met, and the last spike was driven. There was no ceremony, but much jubilation, with the first train from NYC to Montreal through Big Moose just twelve days later, October 24, 1892.

Webb’s Nehasane Lodge & Preserve

Webb’s family connection with the Vanderbilts gave him more than his marriage partner and a career change. It also explained his passion for the Adirondacks and his early experiment with conservation. Throughout the 1880’s Webb made annual trips to the Tupper Lake area to hunt and fish with his new brother-in-law Frederick Vanderbilt, joining together to purchase 10,000 acres to start what they called “The Kildare Club.”

In 1893 Webb built Nehasane Lodge on the shores of Smith’s Lake, which he renamed Lake Lila in honor of his wife. Ne-ha-sa-ne was said to be a Native American term for “crossing on a stick of timber.”

Webb fitted a rail car to take he and his family from his Manhattan office to their remote refuge, entertaining friends and relatives for many years during the fishing and hunting seasons.

In his new capacity as a business leader, he foresaw the profit potential from a shorter connection between the eastern US and Canada. Mass tourism was peaking and the potential for logging revenue for a rail line into virgin timberland was inestimable.

The map here shows two versions of the preserve which Webb incorporated as “The Nehasane Park Association,” in 1894, the bigger 115,000-acre version depicted on an 1894 railroad map (left side) and the scaled down 40,000-acre park from his own 1898 survey (right).

The map here shows two versions of the preserve which Webb incorporated as “The Nehasane Park Association,” in 1894, the bigger 115,000-acre version depicted on an 1894 railroad map (left side) and the scaled down 40,000-acre park from his own 1898 survey (right).

This larger map on the left supports Bill Marleau’s contention that Webb originally wanted to include Big Moose and Twitchell Lakes in his Park. If that had transpired, Twitchell would have become Forest Preserve, off-limits for private development, and this story of its pioneers and history a moot point. Webb descendants sold the Park to New York State in 1979.

With William Seward Webb as Twitchell Lake’s landlord in 1891, Hiram Burke had to obtain permission to host his sporting parties in the cabin he had built. Webb almost certainly had Burke sign a contract for some role as Twitchell’s caretaker before carrying out a final survey and lakefront sale in the late 1890s.

In the meantime, sportsmen and women continued to seek out Twitchell Lake, but things had changed. Only those who applied for and received Webb’s permits were allowed to fish or hunt at Twitchell Lake.

Guide shanties and hotels elsewhere on Webb acreage were less fortunate. They were all knocked down, signs posted forbidding fishing and hunting, and a handful of guides hired as guards to enforce the rules. What had been “fishing and hunting paradise” for more than thirty years was now strictly off-limits.

Webb’s amazing railroad achievement was the main reason Herkimer County renamed Wilmurt “The Town of Webb.” There were a host of sportsmen with a less than favorable view of the Doctor, one of them Big Moose Lake resident and retired minister Aaron Lloyd. When he refused Webb’s $13,000 offer for his 2,240-acre “Triangle” bordering Big Moose Lake, he found himself in double, multi-year lawsuits which in the end invalidated his deed and awarded his land to Webb. You can read this sad but true story at the New York Almanack here.

Three Logging Contracts

Keeping canal boats moving and spring log-drives running remained problematic, particularly with dry summers in the 1890s. Basselin’s 1886 wood-earth dam at Stillwater was raised another five feet in 1893, flooding a good portion of Webb’s refuge and preventing his use of the Beaver River for getting logs to Beaver Falls.

Long stretches of the old Carthage and Champlain Road disappeared underwater. Webb’s threatened 1895 lawsuit against the State took a week just to record testimony in Albany, his attorney Charles Snyder preparing the case to present before the State Board of Claims.

The State brokered a solution, its purchase of affected wilderness areas for $600,000 in return for dropping the suit. Webb accepted and this historic 1896 deed for 74,584 acres became the largest addition to New York’s Forest Preserve to date.

The State brokered a solution, its purchase of affected wilderness areas for $600,000 in return for dropping the suit. Webb accepted and this historic 1896 deed for 74,584 acres became the largest addition to New York’s Forest Preserve to date.

That deed also guaranteed Webb handsome profits from three time-limited lumbering contracts with companies agreeing to work under his terms and covenant. The final 1925 concrete dam at Stillwater raised the reservoir a total of 33.5 feet to create an 11-mile-long body of water impounding up to 35 billion gallons of water.

This Brown’s Tract map of Township 8, surveyed by D. C. Wood, highlights the land Webb sold to the State in yellow, the red-shaded lakefront parcels reserved by Webb for private sales. Twitchell Lake remained his property until 1898, when the first of seven major purchases were made. The largest transfer went to his personal administrator and paymaster William J. Thistlethwaite in 1902.

Twitchell Lake was caught geographically in the middle of the three Webb lumber contracts. To the north, Moynehan Brothers had a good part of Totten & Crossfield’s Township 42.

They probably reused old Prince and Norcross-Saunders lumber camps. Firman Ouderkirk logged from just north of Twitchell up to and beyond Beaver River Station, where he established a huge mill. Both companies were bound to cut their logs in the Ouderkirk mill and ship the dimension lumber to market on the rail line Webb built.

After selling his railroad to the New York Central in 1893, it was renamed the Mohawk & Malone, Webb’s cut on passenger and lumber traffic contractually guaranteed.

The third and largest lumbering contract went to Moose River Lumber Company, headed by Webb’s political ally John A. Dix, the former governor of New York State. Dix had eight years to complete logging Township 8, all logs bound by rail for the mill complex at McKeever, a major station on the Mohawk & Malone.

Twitchell Lake’s Lumber Camp #1 came to life again under the Dix operation, the corduroy road now terminating near Big Moose Station, its sidetrack a major log-loading area. Spruce, hemlock, and white pine outputs at the McKeever mill for 1896, the year the contract began, were 5.5 million board feet, increasing each year thereafter.

Twitchell Lake’s Lumber Camp #1 came to life again under the Dix operation, the corduroy road now terminating near Big Moose Station, its sidetrack a major log-loading area. Spruce, hemlock, and white pine outputs at the McKeever mill for 1896, the year the contract began, were 5.5 million board feet, increasing each year thereafter.

This logging deal also birthed a second lumber camp on the eastern inlet to Oswego Pond, right on the original trail from the Carthage and Champlain Road to Twitchell Lake.

Lumber Camp #2

Technically, Lumber Camp #2 fell under the Dix contract. But with no easy way to extract logs except down Oswego outlet and through Twitchell Lake, it is likely that Dix subcontracted Ouderkirk to harvest all the virgin wilderness north of Twitchell, starting in 1896. Ouderkirk ran a major camp at Lonis Falls on the Terror Lake trail, with a lumber road to his mill at Beaver River Station.

Extending this road to Lumber Camp #2 was a strait shot for use of winter horse-drawn log-sleds. Steel runners still hang on a tree, with this broken double-bit axe head dug up on location, along with slag from the blacksmith shop or cooking shed, assorted old bottles, sled and saw parts, and an old coffee pot and frying pan.

By 1890, the two-man crosscut saw began to replace the double-bit axe for felling trees. Norman Burt Sherry, Sr., an early Twitchell camp owner, took his children on “tramps” to view Lumber Camp #2 in 1921, the buildings still standing at that time.

Surveyed & Sold for Summer Use

Surveyed & Sold for Summer Use

William Seward Webb retained Herkimer civil engineer David C. Wood as his personal surveyor, employing him for multiple projects. The Herkimer Democrat added road-builder to Wood’s titles, noting he was approved by the Town of Webb’s Board of Supervisors “to lay out, construct, build and grade a public highway … that road making a continuous highway from Old Forge to Raquette Lake.”

Secondly, Wood testified on behalf of Webb in important Adirondack land court cases, often certifying land boundaries. In fact, Fulton Chain historian Charles Herr noted this: “Wood’s knowledge of the Adirondack lands and his ability to confirm old boundary lines led to an appointment as Chief Land Surveyor for the State’s forest and land division for over 20 years.”

Most of the surveys done in this era and region were signed by D. C. Wood. Per Webb’s instruction, Wood surveyed Township 8 in 1892, laying out Land Parcels A through F, sold in 1896 to New York State, but retaining all lakefront properties to put up for sale. Wood led a crew to mark off these lots in 100-foot lengths, Twitchell Lake divided into 171 lots as shown on this enlargement of the original Wood map.

In 1898 two hotels were founded at Twitchell. A fishing enthusiast named Truman S. Skilton purchased 34 lots (green) for his Skilton Lodge. Skilton ran a Winstead, CT, business that marketed fishing products — reels, lures, fly rods, and tackle – direct and by mail order, following his passion for trout fishing and preservation.

On his 217-acre purchase he built a family lodge, resort cottages, and a sawmill, advertising to “the ‘sports’ who sought peace, tranquility, and trout in the solitude of the Adirondack wilderness.”

Rufus E. Holmes, also from Winstead, purchased property from Webb in 1901 and had a camp built (dark blue). He may have been the Skilton’s banker. Interestingly, Holmes was an early member of The Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, formed in 1901 for “the preservation of the beauty of our unequaled natural Park.”

The other hotel was Earl Covey’s, patterned after his father Henry’s Camp Crag on Big Moose Lake. Earl built the historic Twitchell Lake Inn on one of his 23 lots (red), cottages for guests on most of the other parcels. Earl learned his half-log palisade method of construction from his father, a style brought to the Adirondacks by French-Canadian lumberjacks.

Accordingly, the four walls were formed by half-logs secured on top of a milled timber sill. Up to 20 of the cottages on Twitchell Lake, in addition to the Inn’s guest cabins, were built by this method. In 1910 he added a gasoline-powered circular sawmill on lots 7 and 8, hence its name “Sawdust Bay.”

Earl assisted the original survey party in laying out Twitchell lots, extended from lines marked on the ice, then with stakes every 500 feet along the shoreline. A compass was used to blaze the rest of the boundary back to wood stakes on the State line. Disputes arose years later because the compass lines did not always line up with the lakefront markers.

This ad in New York City’s Evening Post suggests that Twitchell’s early settlement included a flood of summer visitors, served by daily trains, who discovered and then became loyal patrons of these hotels. Access to Twitchell Lake totally shifted, Stillwater Reservoir cutting off the former trails from the NW, the new “Twitchell Lake Road” connecting the lake’s SE “Public Landing” with Big Moose Station.

Dwight B. Sperry won the contract for building the two-mile road from Big Moose Station to Twitchell Lake for $10,400. Also, in 1905 the Big Moose Transportation Company was incorporated with its stagecoach service to move tourists, summer residents, and lumberjacks, back and forth. Earl Covey was one of the drivers for this company, here posing with lake residents on the bridge over Twitchell Creek.

The earliest purchase from Webb was made by Rev. Dwight Jordan, a Methodist-Episcopal pastor from Brooklyn, NY, who hunted deer with his wife for some seasons before purchasing two lots (brown).

He invited fellow clergymen, Eugene Noble and Fairbank Stockdale, to join him at Twitchell, their camps built on the blue and pink lots, respectively. Tragically, Jordan blinded his wife in one eye testing his rifle before the 1905 deer season, but they continued to vacation in their log cabin for many years.

Sixty percent of Twitchell shoreline remained under Webb ownership until 1902 when his secretary, William Thistlethwaite, purchased the remaining 102 lots (yellow), more than 400 acres. Settling in Old Forge as a real estate developer, he purchased most of the lakefront lots in Township 8, including Big Moose and Fourth Lakes. Thistlethwaite had plans to log all those lots before selling them as summer cottages, a kind of double profit from his investment.

Twitchell Lake was saved from the loss of its lakeshore spruce and white pine by a lawsuit brought by the NYS Forest, Fish and Game Commission against Thistlethwaite for logging his pre-sale Fourth Lake lots. The State found him in violation of the Webb Covenant. Twitchell was next. All Thistlethwaite deeds for Twitchell sales confirm this, logging rights clearly spelled out:

“Reserving to the party of the first [Thistlethwaite] … the right to float logs, timber and pulpwood down and through said lake and past said premises … together with the right of [Thistlethwaite] to dam up the waters of said lake whenever desirable for the purpose of driving logs either above or below said lands (41 of his lots were conveyed to Patrick J. Harney, dated June 5, 1907).”

“Reserving to the party of the first [Thistlethwaite] … the right to float logs, timber and pulpwood down and through said lake and past said premises … together with the right of [Thistlethwaite] to dam up the waters of said lake whenever desirable for the purpose of driving logs either above or below said lands (41 of his lots were conveyed to Patrick J. Harney, dated June 5, 1907).”

It is hard to imagine Twitchell Lake dammed up, six to twelve feet above normal level and full of logs, a sluice gate opened in the outlet dam to flood logs down Twitchell Creek to a transfer point near Big Moose Station, for loading onto the Mohawk & Malone. That is exactly what Thistlethwaite contracted his Hinckley Fibre Company to do, these deeds authorizing such action. The State put a stop to it with its 1907 suit.

Reflecting on Twitchell Lake Settlement

Shortly after the turn of the century, Twitchell Lake was well on its way to settlement, its original seven residents established, summer tourists arriving by stagecoach from Big Moose Station, and a host of new lots up for sale by Thistlethwaite and Harney.

Two Adirondack guides, Francis Young and Low Hamilton, shut out of their trade by Stillwater Reservoir, settled on lots they purchased from Skilton in 1901. A third hotel was added to the lake’s two by Low Hamilton’s wife Myra, who got him to build her a tearoom above their boathouse. Ownership of Lone Pine Camps later passed to the Hamilton’s son-in-law Fred Elmers, who transported guests and delivered mail in his classic boat, The Dutchess.

Three more early settlers purchased their lots from Thistlethwaite — the Holy Cross Club in 1902, the Shattock’s in 1904, and the Slayton’s in 1905. Before their purchase of a lot, the Men’s Club of the Church of the Holy Cross in Utica, NY, regularly camped out at Twitchell, a spiritual retreat complete with fresh trout and venison.

They named their camp “Holy Cross Lodge.” Many of the later settlers who purchased lots for camps first summered at Skilton Lodge or Twitchell Lake Inn. These pioneers and guests together formed a lake community that has grown, changed, and deepened over the years.

Twitchell Lake truly has benefited from its remote wilderness location, the lumber industry arriving late in Adirondack terms. Paul Crouch celebrated the east shoreline of Twitchell as “one of the most beautiful shores in the Adirondacks,” its spruces well over 200 years old.

He attributed this to two early families, the Nobles and Herbens, who held onto their properties for over 60 years. Medical doctor George F. Herben married Beatrice Slayton, also a doctor, the first wedding to be held at Twitchell. But there was another factor involved, Webb’s Nehasane Park experiment in conservation.

Webb’s brother-in-law Frederick Vanderbilt introduced him to Gifford Pinchot, soon to be appointed for twelve years as U.S. Forester in Washington, DC. In 1896, Webb invited Pinchot to run a two-year experiment in conservation, “to demonstrate the wisdom of removing only the mature timber and leaving plenty of trees, under proper seed-producing conditions, to perpetuate the forests.”

These “principles of scientific forestry” made such good business sense to him, that he crafted these into what has become known as “the Webb Covenant.”

This covenant has been incorporated into all the early cottage and hotel deeds for the Twitchell, Big Moose, and Fourth Lake allotments, with stipulations about forest fire prevention, public access to all trails on private lands, and the exclusion of any commercial, agricultural, or manufacturing projects on or near those lakes. Specifically, lumber roads and camps were to be sited no closer to a lake than half a mile, Lumber Camps 1 & 2 just over that distance from Twitchell’s shore.

This covenant has been incorporated into all the early cottage and hotel deeds for the Twitchell, Big Moose, and Fourth Lake allotments, with stipulations about forest fire prevention, public access to all trails on private lands, and the exclusion of any commercial, agricultural, or manufacturing projects on or near those lakes. Specifically, lumber roads and camps were to be sited no closer to a lake than half a mile, Lumber Camps 1 & 2 just over that distance from Twitchell’s shore.

Twitchell Lake clearly dodged several “bullets,” projects that would have exposed it to hyper-development, including canal, logging, and railroad schemes that never materialized.

That fortunate trend continued in 1923 when a major public proposal called for a State road named “Beaver River Highway” to run right along the west shore of Twitchell Lake, as a 1923 Journal & Republican reported:

“Lowville and Lewis county are to have an improved road into the heart of the Adirondacks, via Number Four and Beaver River to Twitchell Lake, connecting with the Old Forge-Big Moose system of state highways as soon as the business and hotel men in both sections can secure it.”

While all the hoteliers supported the proposal, two barriers remained – getting cars across Stillwater Reservoir and gaining a Constitutional amendment to cut timber between Beaver River and Twitchell. This project never came to pass, preserving Twitchell’s unique wilderness character.

The arrival of the Webb railroad in 1892 was a game changer, with as many as eight to ten trains a day bringing tourists to rustic mountain stations like Big Moose during the peak summer season.

Twitchell Lake settlement clearly reversed a trend pointed out by Barbara McMartin, that 22% of the Adirondack wilderness was locked up in wealthy private preserves like that of Nehasane Park. Not so Twitchell, where settlement included clergy, guides, sportsmen and women, and everyday Americans seeking retreat from urban centers and a fresh experience of nature and the wilderness.

This Adirondack Park Agency map titled “125 Years” shows how the Forest Preserve, established in 1885, has grown, lighter green parcels added to the darker green core over that timeframe. The red feature shows the largest addition to the Forest Preserve with Webb’s 1896 sale to the State.

That sale surrounded Twitchell Lake in Forest Preserve, framing and highlighting a real gem in its wild and beautiful setting. Twitchell’s pioneers and current lake residents have worked hard to keep it that way.

Read more about Twitchell Lake.