It was a cold wintry night in early January 1793 in Upstate New York when a trio of political operatives reined in their horses at the home of John Van Alen. The two story wood framed farmhouse stood in newly formed Rensselaer County on the east side of Hudson River.

It was a cold wintry night in early January 1793 in Upstate New York when a trio of political operatives reined in their horses at the home of John Van Alen. The two story wood framed farmhouse stood in newly formed Rensselaer County on the east side of Hudson River.

One of the men, John Van Valkenburgh struggled with a box and several canvas bound books. Once inside the house, the weary Dutchman was approached by Van Alen’s wife, lugging a large chest. Anne Van Alen suggested the chest could be used to store the important items Van Valkenburgh was manhandling.

Grateful for the help, he eagerly stowed the contents in the chest for the night. He carefully locked the chest with a key which he kept “in his breeches pocket” as he slept the rest of the night in Van Alen’s house.

What could go wrong? Cynics may wonder why the chest was secured at a house owned by the Federalist candidate up for election in a hotly contested congressional seat. The close race between Van Alen and his Jeffersonian backed opponent, Henry Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, would generate accusations of vote tampering, corruption and fraud. These charges would make their way to the very halls of the U.S. Congress eleven months later.

What could go wrong? Cynics may wonder why the chest was secured at a house owned by the Federalist candidate up for election in a hotly contested congressional seat. The close race between Van Alen and his Jeffersonian backed opponent, Henry Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, would generate accusations of vote tampering, corruption and fraud. These charges would make their way to the very halls of the U.S. Congress eleven months later.

The contentious 2020 and recent 2024 presidential elections have been fraught with claims “ballot harvesting” operations, extra ballots suddenly showing up in suspicious suitcases, computer program glitches that could change vote totals in the blink of a nanosecond, bomb threats to discourage voter turnout and non-citizens on voter rolls ready to cast ballots.

But is alleged election rigging and voter fraud a new phenomenon in our country’s history? Hardly so. Shortly after the U.S. Constitution set up our current form of government, clever politicians began to work the system to ensure their own success.

Nearly two hundred and thirty years ago, with the new republic experiencing growing pains, a disputed New York State congressional race shows us that things have not really changed much in two centuries.

The year 1792 was a time when political parties were evolving. Four years earlier, George Washington was the undisputed leader of the American republic. The victorious military leader of the War for Independence needed no party apparatus to gain the presidency. Washington was chosen unanimously in 1788.

The first president would later eschew political parties. Washington’s Farewell Address in 1796 condemned political parties because “they are likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people.”

But four years earlier, however, it was a different story in the new nation. The men who fought the Revolution and ascribed to the principles of a republican system of government figured that political power was as important as the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Staying in control of the early republic’s government meant winning elections. And political parties would be the vehicle to maintaining such power.

As the country matured, men with different political agendas saw themselves divided along two ideological lines. Those who favored a strong central government became known as Federalists. Aligning with this philosophy were founders like Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Philip Schuyler, John Jay and Washington himself.

As the country matured, men with different political agendas saw themselves divided along two ideological lines. Those who favored a strong central government became known as Federalists. Aligning with this philosophy were founders like Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Philip Schuyler, John Jay and Washington himself.

Their principles included a responsible fiscal policy, a national bank, tariffs, industrialization and cordial relations with their former foe, Great Britain. Most founders adhered to these ideas which they sought to promote through a broad interpretation of the Constitution.

Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, New York’s governor George Clinton and other leaders, who based their wealth in land and agriculture, supported a weaker federal government with limited ability to tax, friendly relations with America’s greatest ally during the war, France and a narrow interpretation of the Constitution. Jefferson’s followers became known as the Democratic-Republicans.

The first election under the new Constitution gave the Federalists a resounding majority in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Jefferson’s supporters began to see that gaining power in the new government could only be achieved through strengthening party affiliation.

Four years after the 1788 election, Federalists and Democratic-Republicans squared off for their next real shot at power—the election of 1792.

New York State would be a hot bed of rivalry as one particular congressional district demonstrates. New York had recently formed two new counties into one congressional district: Rensselaer County which represented the interest of the old Dutch patroons, an aristocracy well represented by the Federalists and Clinton County near the Canadian border which contained men inclined toward Jeffersonian ideals.

The congressional contest to represent Rensselaer and Clinton counties played out in January 1793. The Federalist candidate, John Evert Van Alen handily beat his Jeffersonian opponent, Henry Van Rensselaer by a significant majority, 1165 to 870. A third candidate, Thomas Sickles garnered a mere .6% of the vote.

The beaten Republican candidate, Van Rensselaer charged his opponent, Van Alen with fraud. But did Van Rensselaer’s allegations hold water? Perhaps some of Van Alen’s choices during the fight for independence gave Van Rensselaer reason to question his character.

The beaten Republican candidate, Van Rensselaer charged his opponent, Van Alen with fraud. But did Van Rensselaer’s allegations hold water? Perhaps some of Van Alen’s choices during the fight for independence gave Van Rensselaer reason to question his character.

Van Alen’s background prior to the election appears somewhat dubious. Born in 1749, Van Alen became a prominent surveyor, farmer and merchant in the Albany area. In 1778 he purchased 400 acres of land on the east side of the Hudson River where he built a house that still stands today.

Although his name appears on muster rolls of the Albany County militia, Van Alen was jailed in 1777 because he requested time to consider taking an oath of allegiance to New York and the United States.

Once the British were defeated at Saratoga, Van Alen saw the light, took the loyalty oath and was released from prison in November 1777.

After the war, Van Alen seems to have reformed his waffling political position because in 1791, he was made justice of the peace and assistant judge of the newly formed Rensselaer County, the boundaries of which he had surveyed. When Van Alen sought elective office, he had the strong backing of a prominent Federalist, Stephen Van Rensselaer III, the Patroon of Rensselaerwyck Manor.

At 28, Stephen Van Rensselaer was already deeply involved in state and national politics in 1792. Linked to the well-connected Schuyler family by marriage to General Philip Schuyler’s third daughter, Peggy, Stephen sought and won political office in both New York’s Assembly and Senate.

Marriage also gave him firsthand access to the general’s other son-in-law, the political architect of the Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton. Stephen would later serve as lieutenant governor and in the U. S. House of Representatives.

Marriage also gave him firsthand access to the general’s other son-in-law, the political architect of the Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton. Stephen would later serve as lieutenant governor and in the U. S. House of Representatives.

As patroon, Stephen used his vast wealth to found the prestigious engineering school, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and died the tenth richest man in American history, according to Forbes magazine. Stephen Van Rensselaer was a potent ally to have on your side in any political contest.

Unlike his younger opponent Van Alen, Henry Van Rensselaer, Stephen’s cousin, was a bona fide Revolutionary War hero. As colonel of the 4th Albany Regiment, he delivered a pivotal blow to the British army at the Battle of Fort Anne in July 1777.

During the slugfest, the colonel was dangerously wounded when a musket ball pieced his thigh, breaking his femur. Undeterred, the militia commander urged his men forward. His actions at Fort Ann set British general John Burgoyne’s army back several weeks in its march towards Albany. After the war, Henry served in the New York State Assembly.

In 1792, New York’s legislature reapportioned its voting districts, creating new counties and expanding congressional districts to ten, but didn’t complete the job until mid-December. This left little time for candidates to develop their positions in the newspapers; plus, it was difficult to get around in the dead of winter. Voters would have to rely on a candidate’s past performance or connections. Van Alen relied on his ties to the wealthy Patroon of Rensselaerwyck to push his message.

The endorsement of Stephen Van Rensselaer was key to a Federalist victory in the newly formed Rensselaer-Clinton congressional district. Rensselaerwyck was the largest of all New York’s manors with 3,000 tenants. The patroon commanded respect as well as loyalty.

It is plausible to conclude that Stephen urged his tenant farmers to vote for his choice in the election, since Rensselaer County delivered the deciding majority for Van Alen in 1793. But the patroon always denied he had proposed lawsuits against tenants who failed to vote his way. Nevertheless, one source felt “the people of the Manor have been influenced by the Patroon.”

To ensure victory in far-flung Clinton County, the patroon sent his factotum, Thomas Whitbeck to garner votes for Van Alen. As campaign manager for Van Alen, Whitbeck promised to deliver a majority in a sparsely populated wilderness. However, M. T. Woolsey learned from his brother-in-law, Gilbert Livingston that the “true candidate” was Henry Van Rensselaer, so the Democratic-Republicans orchestrated plans against Whitbeck to thwart Van Alen’s chances.

As a result, on election day the Republicans brought in 128 votes with all but one for Henry Van Rensselaer. When all the votes in Clinton County were tallied, the Jeffersonian candidate walked away with a 214 to 32 victory. But the other new area, Rensselaer County squarely went for the Federalist candidate, where Van Alen gained a winning majority.

Van Alen trotted off to Philadelphia while Henry Van Rensselaer was dumbstruck at his loss. So, the loser did what any modern-day politician would do; in this case, he petitioned the United States House of Representatives, complaining of “an undue election and return of John E. Van Alen” to Congress.

Van Rensselaer claimed in one town, there were more votes for Van Alen than names actually counted on the canvas. Sound familiar? In another town, the challenger charged that the ballot box was not locked as per the law, but only tied up with tape. A third complaint, perhaps the most egress, stated that Van Alen, while not a duly constituted election inspector, “had in his possession the ballot box of the town of Rensselaerwyck.”

Despite these serious fraud charges, it took almost a year for a congressional report on the allegations to be completed. Then Congress tabled the report on December 20, 1793.

During this interim eleven month period, the patroon’s political handyman, Thomas Whitbeck was busily working to produce evidence in favor of Van Alen. He reassured the new congressman that Henry Van Rensselaer’s protests were nothing to worry about.

Whitbeck claimed the inspectors at the Stephentown poll were “all Men of Principle and the chosen Men of the Town” who could never have been responsible for such a “Villain’s act as the changing of the Ballot.” Whitbeck had already started collecting sworn affidavits from Rensselaerwyck election inspectors.

John Van Valkenburgh swore an oath as an inspector that he took poll books to Van Alen’s house on the evening of January 6, 1793, but they were safely locked in a chest provided by the candidate’s wife. The next day the chest was opened, the ballot box was taken to Abner Newton’s house where more votes were cast. A board of inspectors at Newton’s house fully approved of Van Valkenburgh’s actions, claiming the ballot box was perfectly safe at Van Alen’s house the night before.

Aaron Ostrander testified he personally sealed the ballot box. The next day his seal was found to be unbroken. Jacob Barhyt and Jacob Schermerhorn admitted they, too, spent the night at Van Alen’s. Their testimony agreed totally with the stories propagated by Van Valkenburgh and Ostander. In fact, Schermerhorn explicitly claimed Van Valkenburgh “kept the key in his breeches pocket and . . . slept with his breeches on during the said night.”

The patroon’s point man, Whitbeck then went to the Crowfoot Tavern in Stephentown where election inspectors and the town clerk assured Whitbeck they were satisfied that no attempt by Henry Van Rensselaer’s supporters could upset Van Alen’s commanding lead. In Lansingburgh, it was the same story — no foul play here. There would be no breaking ranks on the Federalist side to cripple Van Alen’s chances.

On December 20, 1793 the U.S. House of Representatives again took up the question of Henry Van Rensselaer’s petition eleven months after his complaint. It would be an uphill battle for the Jeffersonians because the Federalists squarely influenced the Congress.

Richard Bland Lee of Virginia, younger brother of the famous Revolutionary War cavalryman Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, raised several questions for the House to consider. Lee wanted to know if the irregularities raised in Van Rensselaer’s challenge were sufficient to nullify the election results because New York law did not deem them sufficient.

Lee figured none of the irregularities were sufficient “to vitiate the returns of the votes made by the inspectors, who were sworn officers, and subject to pains and penalties for failure of duty.” If New York law was “to be observed as a sovereign rule of this occasion, the allegations do not state any facts be necessary as to require the interference of the House of Representatives,” Lee posited.

Moreover, since it was an “indispensable requisite” of representative government that a choice should be made at an election, should not the principle be established “that a majority of legal votes, legally given, should decide the election?” Should “partial corruption be sufficient to nullify an election or only that part which was subject to corruption, leaving the election to be decided by the sound votes, however few?” Lee worked his audience masterfully.

Lee’s final question applied a logical conclusion to the arguments he had laid out. If the majority of the votes should be declared sound and since John Van Alen had the plurality of such major part, why shouldn’t this be the criterion for a decision? It was the last point on which the House’s Committee on Elections based its opinion: Van Alen should retain his seat in Congress — or quite simply, there was nothing to see here.

Objections to this opinion immediately peppered Congress from the opposing side. Henry Van Rensselaer’s supporters felt that both houses of Congress had the right to judge the qualifications of their members. New York law was infringing on this right.

Corruption in the Van Alen camp was another objection. It seemed to the Democratic-Republicans that Congress’ report condoned corruption as long as it was on a small scale. Their opinion “observed that corruption in elections was the door at which corruption would creep into the House.”

Contrary to these objections, the standing committee felt that the “time, place and manner” of holding elections was expressly vested in the state legislatures; namely, only New York law was applicable in this case.

Furthermore, Congress didn’t have the delegated authority to judge elections because the states had “different customs” which didn’t allow for congressional control. The election committee also was satisfied that there were no grounds on which to base a charge of fraud. It was apparently no big deal that a ballot box spent a night at a candidate’s house.

Oaths were sworn that the box was not tampered with, so there was nothing wrong there. Van Alen simply could not be charged as an “accessory to any unfair practices in the election.”

A convoluted aspect of New York’s election law indicated that under certain circumstances votes might be rejected or omitted by accident in the general canvas. This was the crux of Henry Van Rensselaer’s argument: he believed that the election inspectors had purposely withheld votes that he was entitled to the previous January. However, the House of Representatives “did not appear ripe for a decision.” Adjournment on the issue seemed to solve a thorny problem.

The House resumed consideration of the committee’s report four days later, but found the report stated that even if there were irregularities in two towns, Van Alen still retained a majority of the remaining votes in the district.

The House finally resolved that Henry Van Rensselaer’s petition did not “state [enough] corruption, nor irregularities of sufficient magnitude, under the law of New York, to invalidate the election and return of John E. Van Alen to serve as a member of this House.” Van Alen was duly seated as a member of Congress.

The House finally resolved that Henry Van Rensselaer’s petition did not “state [enough] corruption, nor irregularities of sufficient magnitude, under the law of New York, to invalidate the election and return of John E. Van Alen to serve as a member of this House.” Van Alen was duly seated as a member of Congress.

Meanwhile, Thomas Whitbeck continued to scurry around the county, obtaining affidavits from election inspectors in several towns supporting his friend, Van Alen. However, these depositions were unnecessary because Van Alen was cleared of any wrongdoing before they reached Philadelphia.

Did Van Alen deserve a clearance from the Congress? There was clearly an indication that “partial corruption” existed in the election. But the election would not be overturned, or a new one held with stricter controls. The Van Alen affair illustrated that the Federalists still held sway in congressional politics, but their power was ebbing as new western districts brought in a majority of Democratic-Republicans.

From the end of the Revolution until the congressional contests of 1792, the legislative branch and the presidency were strongly controlled by American aristocrats. The Federalists would elect another one of their own as president in 1796 with John Adams, but by 1800 Thomas Jefferson and his party would triumph.

With Jefferson’s win, the Federalist Party would fade into obscurity becoming an idiosyncratic artifact in America’s political history.

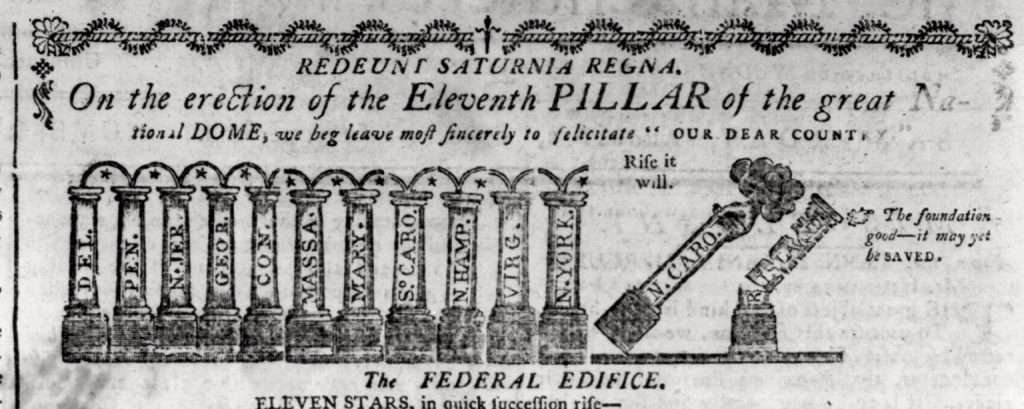

Illustrations, from above: 1796 map of New York by Denison, Morse and Doolittle; Van Alen House, 1793, Washington Avenue Extension, North Greenbush (April 2018); “The Federal Pillars,” from The Massachusetts Centinel, August 2, 1789 (Library of Congress); Revolutionary War service record for John Evert Van Alen (1749-1807); Stephen Van Rensselaer III (Natural Portrait Gallery); and a map showing the First Party System according to the vice presidential election (1792) and presidential election (1796–1816) results (Green shaded states usually voted for the Democratic-Republican Party, while orange shaded states usually voted for the Federalist Party or Federalist affiliated candidates).

John Van Alen’s papers are held by the Albany Institute of History and Art’s library.

Recent Comments