Radical Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced the Civil Rights Act in 1870 as an amendment to a general amnesty bill for former Confederates who had fought against the United States during the Civil War. His bill guaranteed all citizens, regardless of color, access to accommodations, theatres, public schools, churches, and cemeteries. It also forbid the barring of any person from jury service on account of race, and provided that all lawsuits brought under the new law would be tried in federal, not traditionally racist state courts.

Radical Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced the Civil Rights Act in 1870 as an amendment to a general amnesty bill for former Confederates who had fought against the United States during the Civil War. His bill guaranteed all citizens, regardless of color, access to accommodations, theatres, public schools, churches, and cemeteries. It also forbid the barring of any person from jury service on account of race, and provided that all lawsuits brought under the new law would be tried in federal, not traditionally racist state courts.

Sumner predicted that the Civil Rights Act would be the greatest achievement of Reconstruction, saying “Very few measures of equal importance have ever been presented.”

Unfortunately, Sumner did not live to see the fate of his bill. He died of a heart attack in 1874 at the age of 63. “Don’t let the bill fail,” the dying Sumner pleaded to Frederick Douglass and others at his bedside. “You must take care of the civil rights bill.”

In the months following Sumner’s death, Congress debated the bill. Among the most contentious components of the bill were the prohibition of segregation in public schools and the composition of juries.

The Senate passed the bill with a vote of 38 to 26 on February 27, 1875 and it became law on March 1st of that year when it was signed by Ulysses S. Grant.

The new law required: “That all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement; subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of any previous condition of servitude.”

The second section provided that any person denied access to these facilities on account of race would be entitled to monetary restitution under a federal court of law. A number of African Americans subsequently sued businesses that refused to serve Black customers.

The US Supreme Court heard five of those cases in 1883, and in a consolidated case known as the Civil Rights Cases it struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in an 8-1 decision on October 15, 1883.

The US Supreme Court heard five of those cases in 1883, and in a consolidated case known as the Civil Rights Cases it struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in an 8-1 decision on October 15, 1883.

The court claimed that the Fourteenth Amendment, which mandates “equal protection of the laws,” did not apply to private citizens, companies or organizations and that the Constitution granted Congress the right to only regulate the behavior of states, not individuals.

Writing for the majority less than 20 years after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, Justice Joseph Bradley, a native of Berne, Albany County, NY, questioned the necessity and appropriateness of laws aimed at protecting Black people from discrimination:

“When a man has emerged from slavery, and, by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen or a man are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.”

The Civil Rights Cases decision eliminated the only federal law that prohibited racial discrimination by individuals or private businesses and left African Americans who were victims of private discrimination to seek legal recourse in largely racist and white supremacist state courts.

Racial discrimination in housing, restaurants, hotels, theaters, and employment became increasingly entrenched and persisted for generations. The decision foreshadowed the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision in which the Court claimed that separate but equal facilities for Black and White people were constitutional.

It would be more than 80 years before Congress tried again to outlaw discrimination by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Afterward

Afterward

Justice Bradley was also a key vote on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 Presidential Election with the Corrupt Bargain of 1877 ending Reconstruction.

It was due to Bradley’s intervention that white supremacist prisoners charged in the Colfax Massacre of 1873 were freed, after he attended their trial and ruled that the federal law they were charged under was unconstitutional.

The Massacre occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Louisiana when an estimated 62–153 Black militia men were murdered while surrendering to a mob of former Confederate soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan attempting to seize power.

When the Government appealed to the Supreme Court in the case United States v. Cruikshank (1875) the court’s ruling meant that the federal government could not intervene on paramilitary and group attacks on individuals.

This opened the door to increased paramilitary attacks in the South that forced African Americans from office, suppressed black voting, and opened the way for white supremacist takeover of state legislatures, resulting Jim Crow laws and passage of disfranchising constitutions throughout the South.

Bradley’s arguments in opposition of the Civil Rights of Black people and women led Rutgers University, Bradley’s alma mater, to remove his name from a building in 2021, stating “Bradley chose to use his position as a Supreme Court Justice to undo reconstruction, regressing on civil rights and opening a new era of oppression.”

Bradley’s personal, legal, and court papers are archived at the New Jersey Historical Society, where they are open to study.

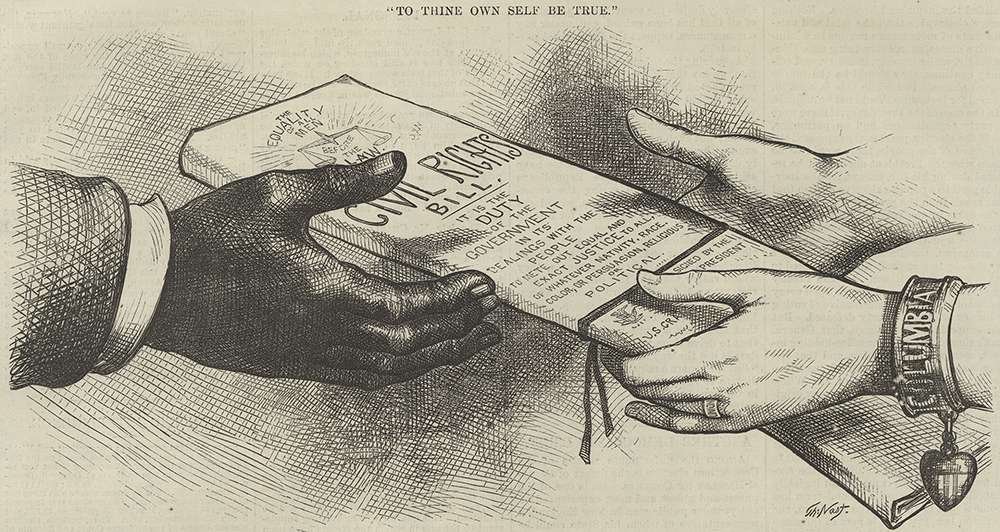

Illustrations, from above: “To Thine Own Self Be True,” referring to the 1875 Civil Rights Act, from Harper’s Weekly, 1875 (NYPL); Justice Joseph Bradley who authored the opinion in the Civil Rights Cases; and “Have White Men Any Rights Left?,” an anti-civil rights cartoon, 1875, (NYPL).

Recent Comments