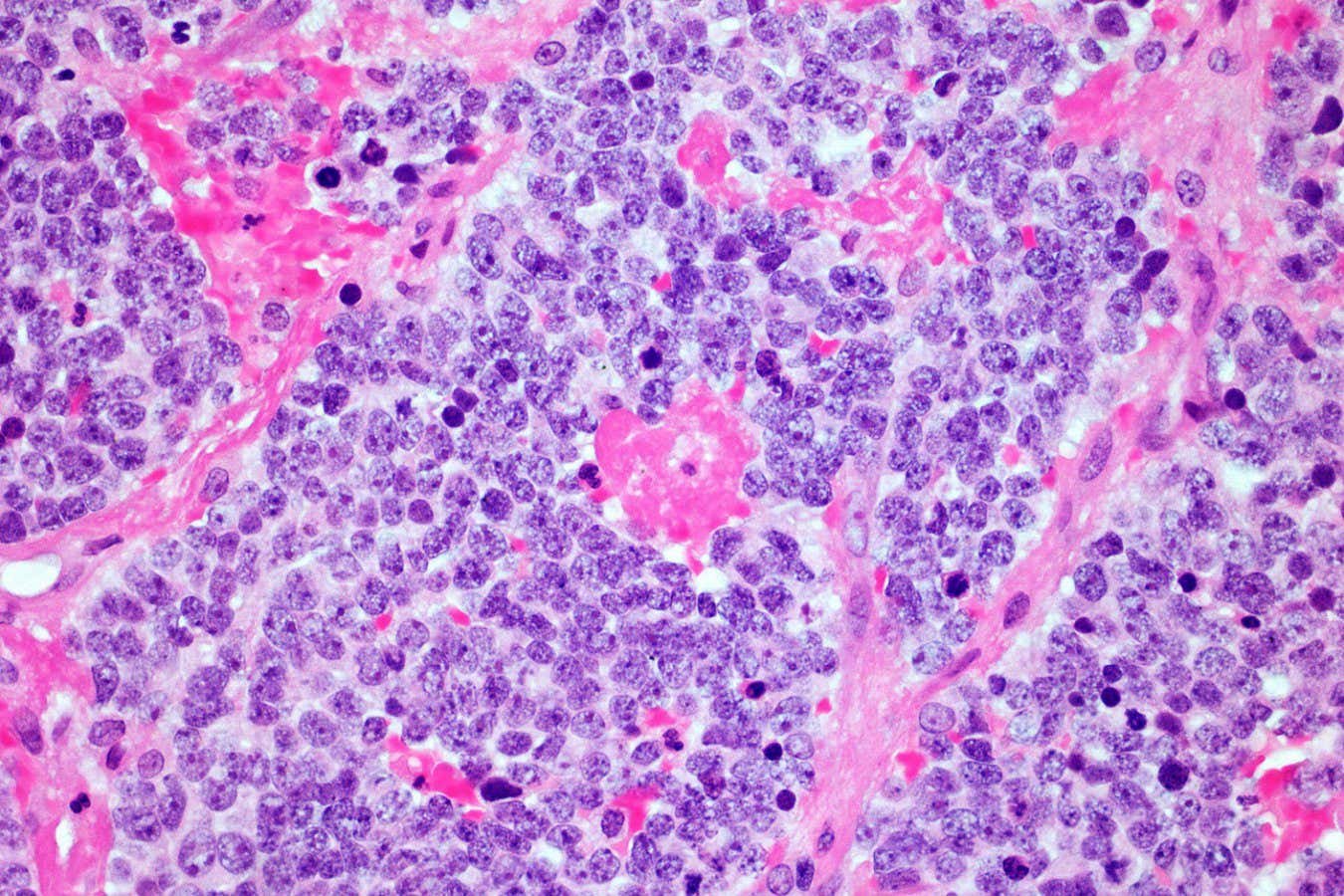

A microscopic image of a neuroblastoma tumour

Simon Belcher/Alamy

A cancer therapy that uses genetically engineered immune cells, called CAR T-cells, has kept a person free of a potentially fatal nerve tumour for a record-breaking 18 years.

“This is, to my knowledge, the longest-lasting complete remission in a patient who received CAR T-cell therapy,” says Karin Straathof at University College London, who wasn’t involved in the treatment. “This patient is cured,” she says.

Doctors use CAR T-cell therapy to treat some kinds of blood cancer, like leukaemia. To do this, they collect a sample of T-cells, which form part of the immune system, from a patient’s blood and genetically engineer them to target and kill cancer cells. They then infuse the modified cells back into the body. In 2022, a follow-up study found that this approach had put two people with leukaemia into remission for around 11 years, a record at the time.

But CAR T-cell therapy usually fails against solid tumours like neuroblastoma, which occurs when developing nerve cells in children turn cancerous, typically before age 5. Such tumours often strongly resist being attacked by the immune system, reducing the effectiveness of the modified T-cells.

This is why Cliona Rooney at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and her colleagues were surprised to find that a person who had neuroblastoma during childhood – who they had treated with CAR T-cell therapy as part of a trial in 2005 – remained cancer-free more than 18 years later. “These results were amazing – to get complete responses in neuroblastomas with this approach is quite unusual,” says Rooney.

The person had received the treatment at age 4 after several rounds of chemotherapy and radiotherapy failed to fully eradicate their cancer. At the time, the team also treated 10 other people with the same condition whose cancer had also relapsed after standard treatment, and they all experienced virtually no side effects, says Rooney. One of these participants showed no signs of cancer nearly nine years later, before they dropped out of the study, making follow-up impossible. The remaining nine participants eventually died due to their cancer, mostly within a few years of receiving the treatment.

It is unclear why some people responded so much better than others. “That’s the $1 million question, we really don’t know why,” says Rooney.

One reason could be that each individual’s T-cells behave slightly differently depending on their genetics, prior exposure to infections and various lifestyle factors, such as their diet, says Rooney. Indeed, the team found that CAR T-cells persisted in the blood for longer in participants who survived for longer.

Another explanation could be that some participants’ tumours were more immunosuppressive and resisted the CAR T-cells more strongly, says Rooney.

Rooney’s team is now exploring new ways to engineer the cells so that they can benefit more people. “We have to improve them and make them more potent, without increasing toxicities,” she says.

Such endeavours are likely to yield further success, says Straathof. “Now we’ve seen a glimpse of what is feasible.”

Topics:

Recent Comments