The term “New World” originated from the late fifteenth century and referred to the recently discovered Americas which astonished Europeans who had previously thought of the world as consisting of Europe, Asia and Africa (the “Old World”).

The term “New World” originated from the late fifteenth century and referred to the recently discovered Americas which astonished Europeans who had previously thought of the world as consisting of Europe, Asia and Africa (the “Old World”).

The earliest accounts of Spanish explorations in Central and South America were written in a series of letters and reports by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera (1457 – 1526), an Italian-born historian and chaplain to the Court of Ferdinand II, King of Aragon, during the Age of Exploration.

In 1530 he penned De orbe novo (On the New World) which describes the first contacts of Europeans and Americans. From the very beginning to the present day “old” versus “new” were not simply descriptive terms, but in many ways value statements – the Old World being superior to the New World or vice versa.

In 1530 he penned De orbe novo (On the New World) which describes the first contacts of Europeans and Americans. From the very beginning to the present day “old” versus “new” were not simply descriptive terms, but in many ways value statements – the Old World being superior to the New World or vice versa.

The ‘A’ Word

In 1896, American physician John Harvey Girdner (1856-1933) published an essay in The North American Review entitled “The Plague of City Noises” in which he analyzed the effect thereof on the mental balance of Manhattan’s inhabitants.

Five years later he published a book on Newyorkitis. Defined as a condition by which mind, soul and body have departed from the “normal,” breeding moral and physical degeneration amongst city dwellers.

European socio-cultural observers feared that a similar epidemic might take hold of the Old Continent. Americanization became an obsession; the “A-word” made critics shiver. There was an undertone of cultural superiority in this anxiety.

An increasing sense of European crisis found expression in an ambiguous attitude towards the emerging might of the United States. Europe suffered from an “America problem” which, in turn, had a depressing effect on its own sense of identity.

Did the United States offer an escape route to exhausted continentals? Was there viable life for the offshoot as the old vine shriveled? Would the grapes of achievement be pressed in California rather than in European vineyards?

Did the United States offer an escape route to exhausted continentals? Was there viable life for the offshoot as the old vine shriveled? Would the grapes of achievement be pressed in California rather than in European vineyards?

Many felt that Europe’s pride and identity were damaged and degraded. Compared to young and energetic America, the Old World appeared stale and stagnant – a museum at best, not an active and forward-looking entity.

By the same token, America suffered from its European heritage. The conflict between inherited forms and living experience has been a persistent element, consciously or unconsciously, in the work of every creative artist who has dealt with the American environment.

It figures strongly in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s writing. He sensed the necessity for new artistic forms suited to the realities of a rapidly developing democratic and industrial social system.

Transit

As Europe became more accessible to American artists after the Civil War, many young painters wished to experience the art and culture of the Old World.

The first wave of American artists in Europe consisted of painters who came to see and study the Old Masters. They undertook traditional training sessions at the great art centers and academies. They were inquisitive and introvert. The experience to them was overwhelming.

As a result, much of their early work mimics the styles of the Old World. Childe Hassam (1859 – 1935) introduced Impressionism to the United States, Marsden Hartley (1877 – 1943) was influenced by Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso and the Cubists, while Theodore Robinson (1852 – 1896) was in tune with Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Amongst the numerous painters who experimented with the different movements they had encountered in Paris or elsewhere in Europe emerged an awareness of cultural identity, a desire among artists to create their own history, a tradition that would match or rival European achievements.

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries American artists were in the process of discovering themselves and searching for a collective identity. As a consequence, historians have tended to view the development of American art in terms of a “transit of civilization” or simply as an extension of European culture.

Increasingly, the “never-ending” comparisons became both an injustice and an irritation to working artists. Abstract Expressionism is widely regarded as America’s first great stride away from the overbearing influence of the European tradition.

The movement was precipitated by Manhattan’s Milton Avery (1885 – 1965) and had inspired many of its proponents (Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb and others). It angered the pioneering painter that critics lazily referred to him as “America’s Matisse.”

Although Continental trends can be traced in American art, there is nevertheless a quality in the sum of creative output that is distinct from the European tradition. The idea that one is but a maimed offshoot of the other proved untenable.

Années folles

Années folles

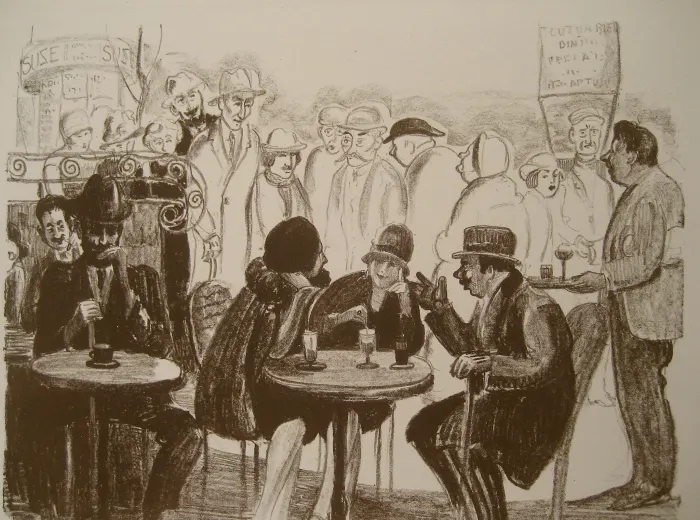

Once the Great War was behind them, Parisians rebounded in a carnival of hedonism known as the “années folles” (crazy years). There was a new aspect to this particular orgy of pleasure: the influx of American writers, artists and musicians who escaped prohibition and puritanical small-mindedness back home. They were drawn to the French capital for its creative vitality and freedom of expression.

The second wave of arrivals in Paris consisted mostly of writers with a completely different mind-set from that of their predecessors. They were self-exiles from the New World who had left a homeland they considered artistically, intellectually and sexually oppressive.

These aspiring authors were drawn to the city for its cultural dynamism, its urge for experimentation, and for its creative space to the individual to find his or her voice.

Moving to Paris in numbers, some of these young men had plenty of cash in their pockets, taking advantage of the strong exchange rate after the collapse of the French currency. Others arrived with the sole ambition of making it as an artist. They were loud, abrasive and most of the time intoxicated. Paris was a party.

Others escaped to seek (and find) sexual liberation. The avant-garde was bankrolled by wealthy lesbian expats such as Natalie Clifford Barney (1876 – 1972), Winnaretta Singer (1865 – 1943), Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946) and others.

Having assumed the traditional role of the Parisian hostess (salonnière), these powerful women acted as curators of young talent having divided the territories of art between them. They were trophy hunters.

Sylvia Beach (1887 – 1962, born Nancy Woodbridge Beach) was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister. In 1901 the family moved to Paris when her father was made minister at the American Church.

The family returned six years later and settled in Princeton. By 1916 she was back in Paris as a student of literature and a lesbian woman seeking independence. Two years later she met her lifelong partner, the writer and bookseller Adrienne Monnier (1892 – 1955).

In 1919 Sylvia Beach opened Shakespeare & Co, a bookshop and lending library specializing in Anglo-American literature. The premise soon became a meeting place for modernist authors and artists.

She was a loyal friend to many struggling writers, including James Joyce. In 1922, he trusted her to produce the first printing of Ulysses where publishers in London and New York City, fearful of prosecution, had refused to touch the novel.

Harlem-on-the-Seine

There was another group of gifted Americans keen to leave the country. In the course of the 1900s Harlem had established itself as a center of African-American culture.

By the early 1920s Black music and theatre were well established. This was a talented but restless generation of artists that felt the urge to escape segregation. By the mid-1920s, many cultural torchbearers had left Harlem for Paris.

One of the first to leave was Louis Mitchell (1885 – 1957), a drummer with a fine tenor voice who had settled in Manhattan in 1912 to create his own band.

One of the first to leave was Louis Mitchell (1885 – 1957), a drummer with a fine tenor voice who had settled in Manhattan in 1912 to create his own band.

His performances at the Café des Beaux-Arts on 40th Street and 6th Avenue were admired by young Irving Berlin. Having spent some time in London, Mitchell settled in Paris. His music took Montmartre by storm.

He encouraged other African-American musicians to come and share in the city’s passion for jazz.

Living in Paris was cheap, club life roaring and alcohol flowing. Most importantly: there were no racial Jim Crow laws. Black Americans arrived in droves, especially after the Volstead Act had gone into effect in January 1920.

The 1926 New York City Cabaret Act, aimed at containing Harlem’s club life, was the final straw.

There were Black writers too who made the journey to Paris, including Langston Hughes (1901 – 1967), one of a group of young African-American authors whose stories and poems dealt with racial themes and taboos that challenged the conventions of a white-oriented literary culture.

Harlem moved to Paris. The impact these newcomers made on local culture was immense. As the artistic climate became increasingly experimental, modernist artists courted Black personalities such as Henry Crowder (1890–1955) and Langston Hughes for their sense of style and vitality. From a cultural point of view their presence provided a boost to French and European art and entertainment.

Transfer

During the twenty-one years from 1919 to 1940 the number of English-speaking authors who lived as expatriates in Paris included some of the most important literary figures of the time.

Henry Valentine Miller (1891 – 1980) was one of the young “nomads” who arrived in the French capital with a “fuck it all” mentality. Born in 1891 at 450 East 85th Street, Manhattan, into a family of Lutheran German immigrants, he had spent the first nine years of his life at 662 Driggs Avenue, Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

A restless and rebellious young man who hated and rejected most of what his parents America stood for, he – like many other talented youngsters of his generation – was desperate to run off.

A restless and rebellious young man who hated and rejected most of what his parents America stood for, he – like many other talented youngsters of his generation – was desperate to run off.

Leaving behind a tempestuous marriage and carrying with him a novel in progress under the title Crazy Cock (the manuscript was rediscovered in 1988 by his biographer Mary Dearborn and published three years later), he settled in Paris in 1930 where – having met her in 1932 – he was supported by his Franco-American lover and fellow writer Anaïs Nin.

To Henry Miller and other young Americans Paris functioned as bar, bedroom and brothel. He intensely enjoyed the city’s relaxed attitude towards erotic entertainment that was symbolized by the emergence of Josephine Baker.

The Afro-American dancer had created a sensation in October 1925 after her debut in the Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées where, dressed in pearls and feathers, she performed her “Danse Sauvage” to a rapturous audience.

Paris acquired the reputation of a hothouse of naughtiness. Miller caught the atmosphere in his writing.

Jack Kahane was born in Manchester in 1887, the son of Rumanian Jewish immigrants. In 1929, he established the Obelisk Press and moved to Paris in order to escape British censorship.

He published pornography to make a living and, at the same time, sponsor the publication of fiction that was considered too risky by other houses, including D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In 1934 he took a gamble to accept Miller’s “unpublishable” novel Tropic of Cancer. The book carried the explicit warning that it must “not be taken into Great Britain or USA.”

The novel set a new standard for graphic sexual language and imagery that shook Anglo-American censorship to the core. It remained banned for a generation, by which time it had become part of post-war cultural folklore.

The novel set a new standard for graphic sexual language and imagery that shook Anglo-American censorship to the core. It remained banned for a generation, by which time it had become part of post-war cultural folklore.

Miller re-interpreted the artist’s role in society. He presented himself as one of the “Renegade Apaches” organizing raids not from the borders of Mexico, but from the Parisian frontiers of a seedy underworld – a rebel in pursuit of a raw urban aesthetic, finding a distinctly American voice in the process.

Expatriate activity had been at its most intense during the 1920s. It taught Paris that the Old World was losing its “superior” status as the realization dawned that American science and technology were progressing rapidly.

The rejection of Yankee materialism in comparison to Europe’s refined civilization was outdated by the 1930s. Another prospect emerged instead, one that projected America as a potential storehouse of the Old World’s imperiled culture – the United States, in the words of Tom Paine, as an “asylum” for persecuted Europeans.

The party faltered on Back Tuesday when on October 29, 1929, stock prices collapsed on Wall Street, ushering in a period of Great Depression in both the United States and Europe.

Most (not all) American writers, artists and entertainers living in Paris left during the 1930s as it became increasingly clear that war was inevitable.

The majority of them settled in Manhattan bringing with them a wealth of ideas and experiences. They revitalized America’s post-war cultural landscape and facilitated the transfer of the avant-garde from Montmartre to Manhattan.

Illustrations, from above: Mabel Dwight “Boulevard des Italiens,” 1927; The illustrated title page of the first edition of De orbe novo (1530); Nelson Beach Greene’s “Newyorkitis,” 1914; La Closerie des Lilas, Le Café de la Société Artistique et Littéraire Française et Etrangère, 171, Boulevard de Montparnasse, Paris, 1909; Louis Mitchell’s band setting Paris alight; Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin; and Paul Colin’s “Josephine Baker,” 1925 (Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery).

Recent Comments